Nursing home debt collection

By the CFPB Office for Older Americans – SEP 09, 2022

Contact the Office for Older Americans: olderamericans@cfpb.gov

Congress created the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB)’s Office of Financial Protection for Older Americans to help older consumers make sound financial decisions as they age, identify and address emerging consumer protection risks, and coordinate these consumer protection efforts with other Federal agencies and State regulators to promote consistent, effective, and efficient enforcement. The Office works to find systemic fixes to emerging risks.

As part of this work, the CFPB conducted an analysis of the risks that nursing home residents and their caregivers face by assessing consumer complaints, nursing home admission contracts, and debt collection lawsuits1 for problematic practices that result in consumer financial harm. The CFPB also learned about nursing home debt collection practices from nursing home experts, legal aid and elder law attorneys, and long-term care ombudspersons from across the nation.

Since its inception, the Office has assisted caregivers supporting older Americans and published research reports, including a recent Data Spotlight on Medical debt among older adults.2 This Issue Spotlight focuses on the risk of financial harm that nursing homes and their debt collectors cause by attempting to collect invalid debts from residents’ family and friends.3, 4

Collecting nursing home bills from family and friends

There are approximately 48 million family members and friends caring for adults with health or functional needs in the United States, and nearly one in six adults is supporting the health and well-being of an older adult through illness or disability.5 Although the Nursing Home Reform Act (NHRA) prevents a nursing home “from requiring a person other than the resident to assume personal responsibility for any cost of the resident’s care,”6 some nursing homes and debt collectors do bill or sue residents’ family members and friends for the cost of care on the basis of their admission contracts.7

If the third party refuses to pay the arrears, some nursing homes hire debt collection firms to demand payment, report the debt to credit reporting companies as the third party’s personal debt, or sue the third party in court.4

During the admissions process, some nursing homes ask or require a person helping the resident gain admission to sign the admission contract as a “Responsible Party” or “Representative.”8 Based on these Responsible Party contract clauses, nursing homes request unpaid balances from third parties. The sums that nursing homes seek to collect range from a few thousand dollars to hundreds of thousands of dollars.9

If the third party refuses to pay, some nursing homes hire debt collection firms to demand payment, report the debt to credit reporting companies as the third party’s personal debt, and sue the third party in court.10 With a judgment, nursing homes can garnish the third party’s wages or foreclose on their home. For some third parties, this can lead to bankruptcy.

The increasing challenge of paying for nursing home care

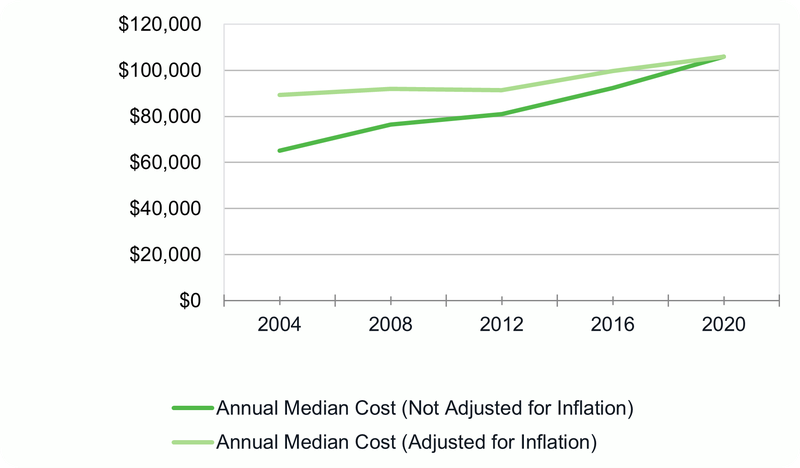

Multiple factors contribute to the likelihood that older adults who need nursing home care will go into debt. Nursing home care is expensive. In 2021, the annual median cost of a single room in a nursing home was $108,405. Between 2004 and 2020, this cost rose by over 60 percent, or 19 percent if adjusted for inflation.11 This price growth has consistently outpaced growth in consumer and medical care prices.12

Figure 1: Median annual cost of a private room in a nursing home

Source: Genworth Financial Inc.,13 with CFPB inflation adjustments using the annual CPI-U from the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

As population changes increase the demand for long-term care, costs are expected to rise.14 By 2060, nearly a quarter of the U.S. population (94.7 million people) will be at least 65 years old.15 After age 65, nearly half of all adults will require some paid long-term services and supports such as a home health aide, assisted living, or nursing home care, and over one-quarter will receive nursing home care.16

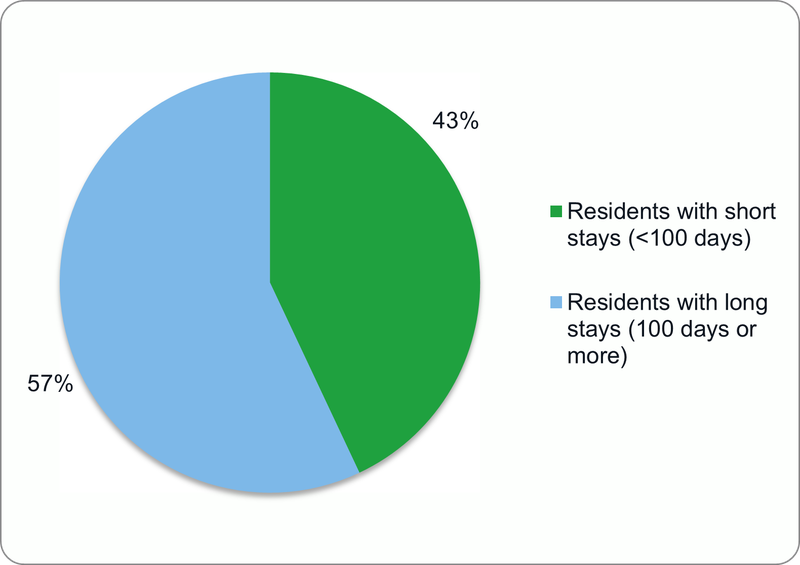

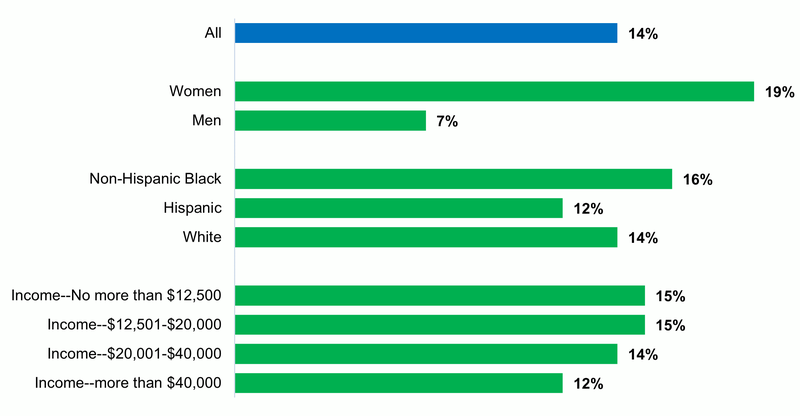

Nursing home residents stay for significant amounts of time. The average nursing home stay among current nursing home residents is 1 year and 4 months, and more than half of current residents have stayed in the nursing home at least 100 days.17 From age 65 on, fifteen percent of older adults are estimated to spend more than two years in a nursing home.18 In addition, life expectancy is expected to rise through 2060.19 With increased life expectancy, older adults are also expected to experience age-related healthcare needs for longer periods.20 The likelihood that an individual will stay in a nursing home for long periods is unevenly distributed, however. Among a group of individuals analyzed from their 70s through the rest of their lives, women, Black individuals, and individuals with lower household income are more likely to need more than 2 years of nursing home care than men, white and Hispanic individuals, and individuals with higher household income, respectively.21

Figure 2: Length of stay among current nursing home residents

Source: CDC National Center for Health Statistics.22

Figure 3: Probability of receiving more than two years of nursing home care, by personal characteristics

Source: Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation (ASPE). Note: This analysis followed adults ages 70-79 who had no more than one limitation on activities of daily living from 1993 through 2014.23

Most older adults are not insured against the costs of long-term care. For example, Medicare, which insures most older adults over the age of 65 regardless of income and assets, has limited coverage based on care needs. Medicare only pays for nursing home care for up to 100 days, and only when the resident requires a relatively high level of “post-acute” care.24 Private health insurance plans that cover the cost of long-term care tend to have similar limitations to Medicare.25 Fewer than 1 in 10 older adults carry long-term care insurance,26 which is unaffordable for many people27 and can carry significant coverage limitations.28 As a result, only a small portion of older adults can afford the out of pocket costs for long-term care without rapidly depleting their savings and accruing debt.29

My Dad had dementia upon entering the first nursing home, so someone had to sign for him, which was me. Only his funds were supposed to be used to pay the nursing home, not mine…

I ended up getting sued for my Dad's nursing home bill, even with the [multiple] insurances… I signed [a settlement agreement] under duress because of a threat of garnishment for the entire amount.30

Medicaid acts as the safety net of last resort for older adults with limited income and assets, and those who have depleted their resources. Sixty-two percent of nursing home residents receive institutional Medicaid assistance,31 which is available to individuals who meet income and asset qualifications. In the vast majority of states, the limitation on countable resources is $2,000 - 3,000 for an unmarried individual.32 For residents who are married, spousal impoverishment provisions protect a certain amount of the couple’s combined resources for the spouse living in the community.33 With institutional Medicaid, residents are responsible for cost-sharing amounts that vary according to their monthly income. Residents may also be responsible for Medicare copayments on non-institutional care (e.g., physician visits, physical therapy, and prescription drugs.34

Since income-eligible residents must deplete their financial resources in order to qualify for Medicaid, residents who apply for coverage during their residency often accrue nursing home debt while they are waiting for the state to process their application.35 The Medicaid application process can take months.36 When applications are denied, residents may appeal, which can also take several months and sometimes years to resolve.37 At this juncture, some nursing homes begin attempting to collect costs from the resident’s family members and friends.38

The nursing home sent my name to the collection agency as if this was a debt accumulated by me. Now the debt collector is jeopardizing my credit with my mother's bill which was suppose[d] to be taken care of by Medicaid and Medicare. The statement from the debt collection company is in my name, with my address… The attachments clearly show that these are not my bills.39

Nursing home admission

For caregivers, the decision to place a family member or friend in a nursing home is frequently made at a difficult time.40 Choices are often limited. The nursing home selected may be the only one located within a reasonable distance from family members or other caregivers. Or it may be the only home with an available bed. This choice constraint may be especially pronounced in rural areas.41

During the nursing home admissions process, caregivers must often sign lengthy admission agreements along with many other documents, such as notices of rights and responsibilities, waivers, and documents related to the resident’s treatment and care. Although many nursing homes treat caregivers with compassion and respect during this difficult step, the caregiver often has no meaningful opportunity to negotiate the agreement even if the caregiver has the time, attention, and ability to read and understand it.

Caregivers themselves may be anxious to complete the paperwork and are likely unaware of the potential legal consequences of what they are signing.42 The admission contracts may be lengthy and contain conflicting and confusing text.43 The nursing home’s representatives may not understand the contracts themselves. Some may convey to caregivers they are only signing the agreement to provide an emergency contact or to facilitate the exchange of information between the nursing home and Medicaid, when in fact the documents indicate that the caregiver is assuming responsibility for payment by signing.44

Responsible party clauses

The NHRA and its implementing regulation prohibit nursing homes that participate in Medicaid or Medicare45 from requesting or requiring that a non-resident personally guarantee the cost of nursing home care as a condition of admission, expedited admission, or continued stay in the facility.46 The prohibition applies to all residents and prospective residents of a nursing facility, regardless of whether they are eligible for Medicare or Medicaid.47 Yet some nursing home admission agreements include clauses that appear to require third parties to pay for residents’ costs.

These clauses vary from contract to contract, but many bear similarities. Regardless of whether these clauses comply with the NHRA, these agreements can lead family members and friends to believe they are legally liable for the resident’s bills.

The CFPB has observed joint and several liability clauses48 in some nursing home admissions contracts. These try to assign to third parties the same personal liability for payment as the resident. Other admissions contracts may request that third parties personally guarantee payment of the resident’s nursing home bills to ensure the resident’s continued stay.49 These clauses may appeal to a caregiver’s emotions by asking “if [they] would like to join others in protecting their loved one from being discharged for non-payment.” Contracts may also be confusing and internally contradictory,50 such as by initially stating that the third party does not guarantee the resident’s costs but later including provisions that appear to make the third party personally liable for non-payment.

The CFPB has also found Medicaid eligibility clauses51 in admissions contracts from nursing homes across the nation. These clauses try to hold third parties personally liable for the resident’s costs if they fail to submit an “accurate, timely, and complete” application for Medicaid.52 In the alternative, responsible party clauses may require third parties to “cooperate” in the Medicaid application process.53 Some nursing homes seek to enforce these requirements by threatening to sue third parties for the resident’s bills if the Medicaid application is denied because it lacked proper documentation.

Many third parties are unaware that the law imposes restrictions on nursing home admissions contracts. They may also lack the resources to properly respond to the lawsuit or find legal representation. As a result, courts may enter default judgments against them. This enables debt collection firms to use wage garnishment or foreclosure to collect residents’ costs from third parties.54

In November 2019, nursing home staff told me Mom’s Medicaid needed to be reinstated, so I went to the office and filled out some more forms. I didn’t hear anything from them about Medicaid for months, so I assumed everything had been taken care of… [I]t was a shock when the nursing home told me in May 2020 that Mom’s Medicaid actually hadn’t been reapproved many months earlier and that I was suddenly on the hook for paying a huge bill.

My Mom passed away on October 3, 2020. It was just two days before … I had received mail which said that I was personally being sued by the nursing home for close to $80,000. I never had time to grieve. I kept so much inside; the stress was unbearable.

I thought, I won’t be able to afford my mortgage – I am definitely going to lose my house. I could face a garnishment of my paycheck and be forced to live on a reduced income when money was already tight to begin with. What will I tell my kids? What does it mean, to have this kind of judgment against you, how will that impact the rest of my life?55

Nursing homes and the debt collectors they hire may also report residents’ nursing home debts to credit reporting companies as a third party’s personal debt.56 This pressure may convince some third parties to enter into payment plans and pay the resident’s debts, even if they have doubts about the legality of the contract.

Claims that caregivers engaged in financial malfeasance

My client had a power of attorney for her friend, a low-income senior with no close relatives. My client met with the nursing home staff and they told her they would be receiving her friend's social security benefits directly to cover what Medicaid didn't. They never sent her a bill. Six months after her friend died, my client received a letter from a local law firm, stating that she owed the nursing home $17,000. My client ignored the letter thinking it was a scam.

The law firm served my client with a lawsuit for over $21,000, alleging she breached the responsible party clause of the admission agreement by not paying her friend’s bills. They also alleged that my client fraudulently conveyed her friend's assets to herself [even though] her friend didn't have any assets to convey.

My client missed her deadline to respond to the lawsuit because she could not afford an attorney to help her and almost ended up with a default judgment against her for $21,000. As a legal aid attorney, I was able to step in quickly and file a motion to dismiss, resulting in the entire case being thrown out.57

In addition to alleging breach of contract, debt collection lawsuits may also claim that a third party has engaged in financial wrongdoing. A majority of the lawsuits against third parties reviewed by the CFPB included claims that either the third party or the resident had intentionally misused, hidden, or stolen the resident’s funds. Other than the fact that the nursing home bills remain unpaid, these claims typically did not include supporting information. This raises the possibility that some lawsuits could be alleging financial malfeasance without justification for the claim and potentially as a technique of coercion.

For example, many lawsuits in New York used the following boilerplate language to allege that third parties had engaged in fraudulent conveyance: “Upon information and belief, from on or about [date of resident admission] through the present, Defendant [name] transferred to himself or as yet unknown third parties monies and other property owned by Resident (the "Transfers"). The Transfers were made by Defendant to himself and others, with actual intent to hinder, delay or defraud Plaintiff, and Resident's other then-present and future creditors.”

In many Ohio lawsuits against third parties, we also found the following boilerplate language alleging fraudulent conveyance: “After [the resident] incurred a debt due and owing [to the nursing home], decedent [resident]’s real property…transferred to the Defendant in exchange for no consideration to the decedent… [on] the date [resident] died. The transfer of the Property to Defendant was made with the actual intent to hinder, delay, or defraud Plaintiff… Alternatively…at the time of the transfer, decedent [resident] had debt or intended to incur, or believe or reasonably should have believed that she would incur debts beyond her ability to pay as they came due.”

Conclusion

Nursing homes play a critical role in caring for older Americans and people with disabilities. However, nursing home care is expensive, and as the number of people who will require this care continues to grow, the cost is expected to continue increasing. With limited coverage options, many older adults who need nursing home care deplete their savings and accrue debt.

Although the NHRA prohibits nursing homes from requesting or requiring a third party to personally guarantee the cost of nursing home care as a condition of admission or continued stay, some nursing home admission agreements include terms that try to hold a third party personally liable for the resident’s nursing home costs. The nursing facilities may engage debt collectors, including law firms, to collect the resident’s unpaid bill from third parties based on these contract terms. Nursing homes and debt collectors may also report residents’ debts to credit reporting companies as the third party’s personal debts. Based on admission agreements, debt collection firms may file lawsuits against third parties claiming breach of contract. Some may also allege financial malfeasance without support. These practices can cause caregivers and their households to experience financial harm.

As discussed in Consumer Financial Protection Circular 2022-05, the practices of nursing homes and the debt collectors they hire may violate federal laws administered by the CFPB and the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS). The CFPB and CMS have released a joint letter urging nursing homes and debt collectors to examine their practices for compliance with federal law.

When residents, advocates, or aging services providers believe that a nursing home is violating the NHRA, they can share this information with their State Department of Health and their State Attorney General. They can also submit a complaint to the CFPB if they believe that a debt collector, such as a company or law firm acting on behalf of a nursing home, may be engaging in unlawful debt collection or credit reporting practices.

Help for nursing home residents and caregivers

Endnotes

-

The CFPB reviewed contracts and debt collection complaints that elder law and consumer attorneys in New York, Ohio, and other states shared with the CFPB.

↩ -

CFPB, Data Spotlight: Medical debt among older adults before the pandemic (May 2022), available at https://www.consumerfinance.gov/data-research/research-reports/data-spotlight-medical-debt-among-older-adults-before-pandemic/full-report/.

↩ -

Some nursing homes may claim that family members are responsible for residents’ costs under state filial support or necessaries statutes. This spotlight does not address such claims. See Katherine C. Pearson, Filial Support Laws in the Modern Era: Domestic and International Comparison of Enforcement Practices for Laws Requiring Adult Children to Support Indigent Parents, 20 Elder L.J. 269 (June 8, 2012), https://elibrary.law.psu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1034&context=fac_works .

↩ -

See, e.g., CFPB Consumer Complaint 4984687, https://www.consumerfinance.gov/data-research/consumer-complaints/search/detail/4984687; Consumer Complaint 4618731, https://www.consumerfinance.gov/data-research/consumer-complaints/search/detail/4618731; Consumer Complaint 3798094, https://www.consumerfinance.gov/data-research/consumer-complaints/search/detail/3798094; Consumer Complaint 2425193, https://www.consumerfinance.gov/data-research/consumer-complaints/search/detail/2425193. See also note 7, infra.

↩ -

Approximately 19 percent of U.S. adults are caregivers for an adult with health needs or functional limitations, and 17 percent of U.S. adults (41.8 million) are caregivers for someone ages 50 and older. AARP & Nat’l Alliance for Caregiving, Caregiving in the U.S. 2020 4 (May 2020), available at https://www.aarp.org/content/dam/aarp/ppi/2020/05/full-report-caregiving-in-the-united-states.doi.10.26419-2Fppi.00103.001.pdf .

↩ -

56 Fed. Reg. 48841 (Sept. 26, 1991).

↩ -

See, e.g., Letter from Chairs of the Federal Advocacy Comm. and State Advocacy Comm., the National Academy of Elder Law Attorneys (NAELA), to Beverly Yang, Older Americans Policy Analyst, Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (July 6, 2022) (on file with author).

↩ -

See Anna Anderson, Defending Nursing Home Collection Lawsuits, Nat’l Consumer Law Center 2 (Nov. 15, 2021), https://library.nclc.org/defending-nursing-home-collection-lawsuits?0=ip_login_no_cache%3D146aa8f25f9bcf00b1cf4ec27a945c4d ; Noam Levey, Nursing homes are suing friends and family to collect on patients’ bills, Nat’l Public Radio (July 28, 2022), https://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2022/07/28/1113134049/nursing-homes-are-suing-friends-and-family-to-collect-on-patients-bills .

↩ -

Levey, supra note 8.

↩ -

See supra notes 7-8.

↩ -

Genworth Financial Inc., Cost of Care Survey: Summary and Methodology 3 (Feb. 2022), https://pro.genworth.com/riiproweb/productinfo/pdf/131168.pdf. CFPB adjusted figures for inflation using annual CPI-U estimates from the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

↩ -

Sean Shenghsiu Huang et al., The Determinants and Variation of Nursing Home Private-Pay Prices: Organizational and Market Structure, 78 Med. Care Res. & Rev. 173 (June 20, 2019), available at https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/1077558719857335 .

↩ -

See Genworth Financial, supra note 11.

↩ -

The core driver of increases in the cost of nursing home services is supply and demand. Id. at 2.

↩ -

The number of adults ages 65 and older is expected to grow from 49.2 million in 2016 to 94.7 million in 2060. This represents a 92 percent increase in the older adult population. By comparison, the population under age 65 is projected to grow by only 13 percent during this time. U.S. Census Bureau, 2017 National Population Projections: Table 2: Projected age and sex composition of the population (2017), https://www.census.gov/data/tables/2017/demo/popproj/2017-summary-tables.html .

↩ -

U.S. Dep’t of Health & Human Services, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation (ASPE), What Is the Lifetime Risk of Needing and Receiving Long-Term Services and Supports? 19 tbl. III (Apr. 2019), https://aspe.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/migrated_legacy_files//188046/LifetimeRisk.pdf . This study uses longitudinal data to estimate the prevalence and likelihood of developing long-term care needs and usage among older adults. It estimates that among adults after age 65, about 48 percent will receive any type of paid care and 28 percent will receive nursing home care at some point.

↩ -

This figure is among current nursing home residents in 2018. This study showed that the average length was 485 days. Given that about two-fifths of residents had short stays (less than 100 days), a portion of residents likely stayed much longer. CDC Nat’l Center for Health Statistics, Post-acute and Long-term Care Providers and Services Users in the United States, 2017–2018, 3:47 Vital & Health Statistics 83 tbl. XIII (May 2022), https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/series/sr_03/sr03-047.pdf .

↩ -

ASPE, supra note 16, at 3.

↩ -

Pre-pandemic U.S. Census Bureau projections in February 2020 suggested that life expectancy was projected to continue growing from 2017 to 2060, though at a slower pace compared to rapid increases between 1970 and 2015. Lauren Medina et al., Living Longer: Historical and Projected Life Expectancy in the United States, 1960 to 2060 3-5 (Feb. 2020), https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2020/demo/p25-1145.pdf . Recent estimates from the National Center for Health Statistics showed that due to increased mortality from COVID-19 and other factors, life expectancy for the overall population declined by 2.7 years between 2019 and 2021, to the lowest level since 1996, 76.1 years. Elizabeth Arias et al., Provisional Life Expectancy Estimates for 2021 7-8 (Aug. 2022), https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/vsrr/vsrr023.pdf . It is unclear how these significant recent declines in life expectancy will affect long-term life expectancy projections.

↩ -

Tracy L. Mitzner et al., Older Adults' Needs for Home Health Care and the Potential for Human Factors Interventions, 53:11 Proc. Hum. Factors & Ergonomics Soc’y Ann. Meeting 718, 718 (Oct. 1, 2009), https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4270052/ .

↩ -

ASPE, supra note 16, 25 tbl.X. Note that these figures on nursing home stays are from a subsample of adults ages 70-79 in 1993 with no more than one limitation of activities of daily living and the study follows them through 2014 to observe the rest of their lives. It therefore excludes some individuals such as those who develop disabilities earlier in life or who do not survive until age 70-79.

↩ -

CDC, supra note 17, at 20.

↩ -

This study is not representative of all older adults because it excludes some people, such as those who developed disabilities before 1993 or those who died before the ages of 70-79. See ASPE, supra note 16.

↩ -

Medicare generally only covers 100 days of skilled nursing facility care when a resident has a prior medically necessary inpatient hospital stay of three consecutive days or more and requires skilled nursing care or rehabilitative services on a daily basis. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, Medicare Coverage of Skilled Nursing Facility Care 14-17 (July 2019), https://www.medicare.gov/Pubs/pdf/10153-Medicare-Skilled-Nursing-Facility-Care.pdf. Under certain circumstances, Medicare also covers short-term, inpatient hospice care or respite care. It does not cover custodial care provided in a nursing home. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, Hospice Care, https://www.medicare.gov/coverage/hospice-care (last visited Sept. 6, 2022).

↩ -

See ASPE, supra note 16.

↩ -

For example, a study looking at newly retired older adults over age 50 in the first years of retirement found that only 6 percent of single adults and 9 percent of couples had long term care insurance. Philip Armour et al., Retirement Security and Financial Decision Making, Rand Educ. & Lab. 12 tbl. 4 (Dec. 2019), https://www.rand.org/pubs/working_papers/WR1224.html . An Urban Institute paper found that only about 11 percent of older adults age 65 and up had long-term care insurance. Richard W. Johnson, Who Is Covered by Private Long-Term Care Insurance?, Urb. Inst. 2 (Aug. 2016), https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/83146/2000881-Who-Is-Covered-by-Private-Long-Term-Care-Insurance.pdf .

↩ -

The long-term care insurance market has contracted significantly, with the number of policies falling substantially and premiums rising among remaining policies, such that they are unaffordable for many older adults. Wealthier individuals, who would have to deplete substantial assets to obtain Medicaid coverage, are likelier to be covered. For example, only 3-4 percent of older adults with household wealth of under $100,000 had coverage in 2014, compared to about 25 percent of older adults with wealth of $1 million or more. Johnson, supra note 26, at 4 tbl. 1. Individuals who are older or have more severe health issues are more likely to be declined for a policy. American Association for Long-Term Care Insurance (AALTCI), Long-Term Care Insurance Facts: Americans with Long-Term Care Insurance Protection 2020 (Jan. 2020), https://www.aaltci.org/long-term-care-insurance/learning-center/ltcfacts-2020.php#2020total .

↩ -

Many long-term care policies have limits on how much they will cover and for how long. U.S. Dep’t of Health & Human Services, Administration for Community Living, What is Long-term Care Insurance? (Feb. 18, 2020), https://acl.gov/ltc/costs-and-who-pays/what-is-long-term-care-insurance .

↩ -

Only 14 percent of older adults, and only 5 percent of older adults with severe long-term services and support needs (at least two functional limitations) have enough income from Social Security, pensions, and other sources to fully cover nursing home care without dipping into savings. U.S. Dep’t of Health & Human Services, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation (ASPE), Assessing the Out-of-Pocket Affordability of Long-Term Services and Supports Research Brief 4-5 (May 14, 2019), https://aspe.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/migrated_legacy_files//189396/OoPAfford.pdf .

↩ -

CFPB Consumer Complaint 2425193, https://www.consumerfinance.gov/data-research/consumer-complaints/search/detail/2425193.

↩ -

See CDC, supra note 17, at 22.

↩ -

Eligibility criteria, including income and asset limits, vary by state. See MaryBeth Musumeci et al., Medicaid Financial Eligibility in Pathways Based on Old Age or Disability in 2022: Findings from a 50-State Survey, Kaiser Fam. Found. (July 11, 2022), https://www.kff.org/report-section/medicaid-financial-eligibility-in-pathways-based-on-old-age-or-disability-in-2022-findings-from-a-50-state-survey .

↩ -

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, Spousal Impoverishment, https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid/eligibility/spousal-impoverishment/index.html (last visited Aug. 30, 2022).

↩ -

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, Cost Sharing out of Pocket Costs, https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid/cost-sharing/cost-sharing-out-pocket-costs/index.html (last visited Aug. 30, 2022).

↩ -

In many states, Medicaid approval can be retroactively applied for up to three months prior to the month of application, depending on when the resident became eligible based on their income and assets. American Council on Aging, How Retroactive Medicaid Coverage Works and Can Help Pay Existing Nursing Home Bills (Feb. 28, 2022), https://www.medicaidplanningassistance.org/retroactive-medicaid/ .

↩ -

American Council on Aging, Medicaid Pending, Nursing Home Care and the Application Process, (Feb. 14, 2022), https://www.medicaidplanningassistance.org/medicaid-pending/ [hereinafter Medicaid Pending].

↩ -

See MaryBeth Musumeci et al., Medicaid and the Uninsured: A Guide to the Medicaid Appeals Process, Kaiser Fam. Found. 13 (Mar. 2012). https://www.kff.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/01/8287.pdf .

↩ -

See Medicaid Pending, supra note 36.

↩ -

CFPB Consumer Complaint 3798094, https://www.consumerfinance.gov/data-research/consumer-complaints/search/detail/3798094.

↩ -

“Choice of a nursing home is often ‘made in an atmosphere of stress and crisis in response to a precipitous deterioration in health status, disability level, or loss of a caregiver or spouse; nursing homes almost always insist on dealing with a family member or responsible party as the principal or only signer of an admission agreement.” Podolsky v. First Healthcare Corp., 50 Cal. App. 4th 632, 652 (1996), citing Donna Ambrogi, Legal Issues in Nursing Home Admissions, 18 Law Med. & Health Care 254, 255, 258 (1990).

↩ -

Rural Policy Research Institute, Nursing Homes in Rural America: A Chartbook 3 (July 2022).

↩ -

“[D]espite the existing federal statutes barring mandatory guarantee agreements, family members are signing agreements without intending to become the private source of payment, and yet are later asked to pay for long term care.” Katherine C. Pearson, The Responsible Thing to Do About “Responsible Party” Provisions in Nursing Home Agreements: A Proposal for Change on Three Fronts, 37 U. Mich. J.L. Reform 757, 783 (2004). See also Anderson, supra note 8, at 2.

↩ -

“During the admissions process, residents or their caretakers face a blizzard of forms that must be signed in order to gain admission.” S. Rep. No. 110-518, at 3 (Oct. 1, 2008), available at https://www.govinfo.gov/app/details/CRPT-110srpt518/summary ; Pearson, supra note 42, at 770 (“Many admissions documents have language which is at best confusing and at worst misleading.”). See also Podolsky, 50 Cal. App. 4th at 638-641.

↩ -

See supra notes 7-8; see also Pearson, supra note 42, at 783.

↩ -

Medicaid is the primary payer for nursing home care. U.S. Dep’t of Health and Human Services, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation (ASPE), An Overview of Long-Term Services and Supports and Medicaid iv (Aug. 7, 2018), https://aspe.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/migrated_legacy_files//182846/LTSSMedicaid.pdf . The NHRA’s requirements apply to at least 94 percent of nursing homes, which have been certified to receive federal payments for both Medicare and Medicaid. Phoenix Voorhies & Kirsten J. Colello, In Focus: Overview of Federally Certified Long-Term Care Facilities, U.S. Cong. Res. Service (May 11, 2020), https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/IF/IF11545 .

↩ -

42 C.F.R. § 483.15(a)(3); see also 42 U.S.C. §§ 1395i-3(c)(5)(A)(ii), 1396r(c)(5)(A)(ii).

↩ -

See 56 Fed. Reg. 48841 (Sept. 26, 1991); see also Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, State Operations Manual, Appendix PP - Guidance to § 483.15(a)(3) (Nov. 22, 2017).

↩ -

For example, an admission agreement from a nursing home provider in Texas includes the clause “Resident or resident representative, by signature on this agreement, acknowledge that both parties are jointly and severally liable for all obligations under this agreement and as such, shall pay all sums due to the facility including the monthly rate and all sums for other services or supplies. Should collection actions be required to secure the payment of any sums due hereunder and be referred to an attorney for collection, the resident and/or resident representative hereunder shall agree to be jointly and severally liable and responsible to pay reasonable attorney fees and collection expenses.”

↩ -

For example, a nursing home provider in Ohio uses language in its admission agreement stating “Many people wish to make sure that care and services to their loved ones are not terminated when the resident does not have the resources to pay for care . . . If the Representative would like to join others in protecting their loved ones from being discharged for non-payment, then he/she should initial “yes” below . . . If the Representative does not wish to protect the resident from being discharged for non-payment, then he/she should initial “no” below. BY INITIALING “YES”, THE REPRESENTATIVE IS AGREEING TO VOLUNTARILY PERSONALLY GUARANTEE PAYMENT TO [PROVIDER], BE JOINTLY SEVERALLY LIABLE FOR SERVICES SUPPLIES RECEIVED BY THE RESIDENT, AND TO MAKE ALL PAYMENTS WHEN THEY COME DUE.”

↩ -

For example, a nursing home provider in Ohio has used an agreement with a no-guarantee provision: “No personal guarantee: The Representative is not personally guaranteeing payment, and nothing in this agreement is to be construed as a personal guarantee of payment.” But the agreement then separately defines “You” to “refer jointly and severally to the Elder and the Representative” and states that “You agree to pay all charges and fees that are billed to You.”

↩ -

For example, a nursing home agreement from a provider in New Jersey includes the following clause: “If Resident/Responsible Party fails to apply for Medicaid benefits in a timely and complete manner, or acts in any way which results in any period of Medicaid ineligibility, Resident/Responsible Party shall be responsible for all charges which are incurred prior to receiving Medicaid benefits . . .” In a separate section, the contract explains that the “Responsible Party . . . assume[s] other legal obligations as set forth in this Agreement and the Responsible Party Agreement and may be held legally responsible for failing to fulfill these obligations.”

↩ -

Elder lawyers and legal aid attorneys reported to CFPB that nursing homes frequently manage the Medicaid application process but sue third parties for the cost of care when the resident’s Medicaid application is denied, even when the denial may be due to the nursing home’s own error. Related clauses require third parties to promise that the resident has not made any disqualifying transfers of their assets within the Medicaid lookback period and try to hold third parties personally responsible if these transfers took place before the resident was admitted, regardless of the third party’s actual knowledge or authority over those transfers.

↩ -

For example, a nursing home agreement from a provider in New York includes the following clause: “The Resident/Responsible Party will fully cooperate with [the nursing home] and the government agencies in the timely completion and processing of any application for public assistance.”

↩ -

See Levey, supra note 8.

↩ -

Economic Impact of the Growing Burden of Medical Debt, Testimony before the U.S. Senate Committee on Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs, 117th Cong. 1-2 (Mar. 29, 2022), (statement of Robyn King, Client of The Legal Aid Society of Cleveland), https://www.banking.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/King%20Testimony%203-29-22.pdf .

↩ -

See supra notes 7-8.

↩ -

Emails from Anna Anderson, Managing Attorney, Legal Assistance of Western New York, to Beverly Yang, Older Americans Policy Analyst, Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (Mar. 25, 2022 & Aug. 30, 2022) (redacted, on file with author).

↩