Big Tech's Role in Contactless Payments: Analysis of Mobile Device Operating Systems and Tap-to-Pay Practices

By the CFPB Office of Competition & Innovation and Office of Markets – SEP 07, 2023

Executive Summary

In jurisdictions around the world, consumers, small businesses, financial institutions, and policymakers are recognizing the benefits of open ecosystems in the digital world. Open ecosystems facilitate easy switching and consumer choice by leveraging both platform interoperability and data portability.

As the United States shifts toward open banking through data portability in consumer finance, the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) is paying greater attention to the potential for platform interoperability, particularly how consumers and those offering financial products and services can access different payment rails.

This issue spotlight focuses on the evolution of payments in point-of-sale (POS) purchases and the role that mobile device operating systems play. Given the continued shift toward the use of contactless payments on mobile devices like smartphones and wearables, there is now readily available technology for consumers to securely make POS payments through different apps and services. However, this evolution means that tech companies are playing a powerful role in determining consumers’ payment options. Any restrictions imposed by the dominant operating systems—Apple’s iOS operating system and Google’s Android operating system—will have an outsized effect on access to payments systems and may hinder the development of a truly open ecosystem.

Given the agency’s mandate to ensure fair, transparent, and competitive markets, as well as the CFPB’s plans to issue rules that will accelerate the shift to open banking in the United States, the CFPB analyzed POS payments in the context of mobile operating systems to better understand the state of platform interoperability in payments, a critical open banking use case. The CFPB’s analysis found that:

- POS payments made through mobile devices are often made using near field communication (NFC) technology. This technology makes it possible to make contactless payments using a mobile device and a checkout terminal. These are often referred to as “contactless” payments or “tap-to-pay.”

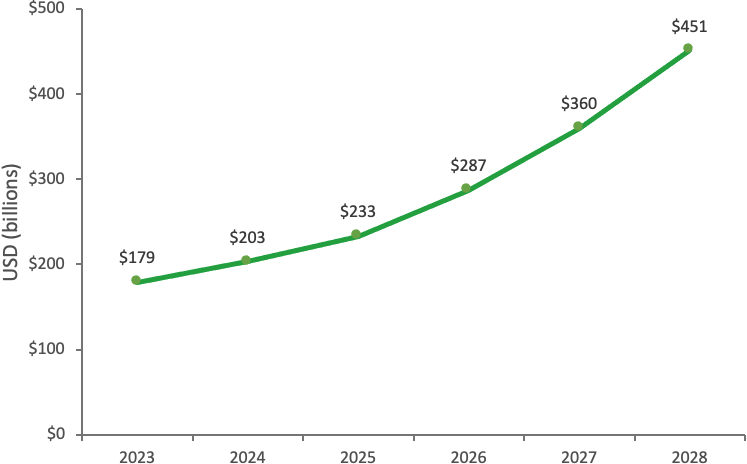

- Use of tap-to-pay at the POS continues to rise in the U.S. as NFC technology has become more commonly included in both mobile devices and payment terminals. This growth is expected to continue—analysts estimate that the value of digital wallet tap-to-pay transactions will grow by over 150 percent by 2028.

- Apple and Google dominate the smartphone operating system market. As adoption of contactless payments on mobile phones continues to increase, these two companies, and the business models and choices they employ, will have profound impacts on the competitiveness of the payments market and the future of open banking.

- While the use of quick response (QR) codes to make POS payments is growing, it is currently less popular in the U.S. than making payments using NFC technology. Payments made through QR codes in the POS context may be less preferred by those making and accepting payments, perhaps due to difficulty of use compared to NFC. QR code payments are also less secure than NFC payments.

- Financial services providers, including bank and nonbank players, can offer applications to facilitate POS payments. However, these apps cannot rely on NFC technology on mobile devices using Apple’s iOS operating system. This includes widely used payment apps such as PayPal, Venmo, and Cash App, all of which are well-positioned to compete in the POS market. Instead, consumers must use Apple’s proprietary payment service, Apple Pay.

- While Google’s Android operating system, which is the other major mobile operating system in the U.S., does not currently restrict access to NFC capabilities, they could reverse this position in the future given their existing market position and relationship with hardware manufacturers.

- Mobile device restrictions such as those related to NFC can inhibit choice and innovation in consumer payments. This type of arrangement may also increase roadblocks to open banking reaching its full potential in the U.S. For example, such restrictions may hinder lower-cost open banking-powered payment innovations, such as emerging services that enable consumers to make point-of-sale transactions using their bank accounts directly.

This issue spotlight is part of the CFPB’s broader effort to monitor the rapidly evolving consumer payments industry, including the expansion of Big Tech companies into this sphere. It is also the first in a series of spotlights focused on threats to robust competition in consumer finance markets.1

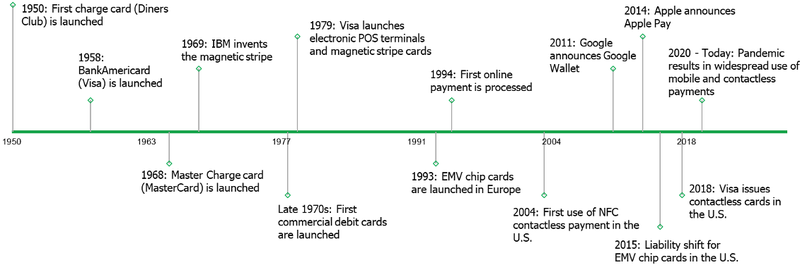

The evolution of POS payments technology

Driven by technological changes, the way consumers pay for goods and services has evolved significantly over the last half-century. In 1970, 16 percent of American households had a credit card; by 1983, that figure increased to 43 percent.2 By 2021, 76 percent of U.S. consumers had a credit card and 87 percent had a debit card.3

New terminals and the addition of magnetic stripes onto cards in the 1970s accelerated the adoption of credit and debit cards, but also contributed to new opportunities for fraudsters to use methods like skimming to steal payment information.4 Despite large losses to fraud, the consumer experience at the POS in the U.S. remained essentially the same until 2015. In that year, the major U.S. networks transitioned to cards embedded with a microchip to encode and protect payment information. (These cards are referred to as EMV (Europay, Mastercard, Visa) cards in the U.S.5) POS terminals were upgraded to accept these cards for more secure “dip and sign” transactions, where consumers inserted the chip directly into the terminal to be safely read. The share of card payment volume in the U.S. using EMV chip cards rapidly grew from two percent in 2015 to 82 percent in 2021.6

The use of NFC technology for tap-to-pay emerged in the U.S. in the 2010s.7 Built off radio-frequency identification technology, NFC uses chips to enable wireless transfers of data between a mobile device or a chip card and a merchant’s POS terminal. The two sides must be within a few centimeters of each other.8 Card issuers rolled out NFC functionality to EMV chip cards in the U.S. in 2018, enabling tap-to-pay transmission of encrypted payment information.9

But even before NFC-enabled cards became widespread in the U.S., the technology was already being developed for use with payment apps on mobile devices—indeed, Google announced the first NFC-enabled payment app (its Google Wallet) in 2011 followed by the Apple Pay digital wallet in 2014.10 With biometric authentication, mobile payments obviate the need to sign a receipt or enter a PIN.11

“Quick response” codes or barcodes, which clerks or customers navigate to and physically scan, have also become popular. For instance, consumers can pay for coffee at Starbucks using a QR code in the Starbucks mobile app that communicates linked payment information to the store’s payment terminal.12 While QR codes were first developed in 1994, it was not until 2017 that smartphone cameras could read QR codes without specialized software.13

Figure 1: POS Payments – Major Launches and Changes

The Evolution of Open Banking

In parallel to the evolution of POS payments, consumers’ ability to share their financial data has also evolved around the world. In some jurisdictions, this evolution has been led by regulatory mandates, often with the explicit aim of increasing competition in consumer finance. In the U.S., market solutions have so far led the way, and this organic growth has made the U.S. open banking ecosystem one of the largest in the world. However, the lack of regulatory structure has also led to persistent disagreements among market participants that have held the ecosystem back from its full potential for consumer benefit. In this context, the CFPB is undertaking a rulemaking required by Section 1033 of the Consumer Financial Protection Act to clarify consumers’ personal financial data rights, which should help to ensure that firms’ competitive interests do not constrain the potential of data portability in financial services.

One area where open banking’s potential could be constrained by incumbents is the payments space, which is both profitable and ripe for disruption. Open banking has already fueled the development of numerous consumer financial products and services that compete with traditional incumbent offerings, including payment products such as peer-to-peer payments and pay-by-bank solutions. These products could benefit from access to NFC functionality and simultaneously compete with dominant mobile wallets and the card networks by facilitating low-cost ACH payments powered by open banking.

Making NFC payments using mobile devices

Today, consumers can use a variety of mobile devices to make tap-to-pay payments at the POS. Most commonly, a user can simply take out their device, wave it close to an NFC-enabled terminal, and confirm the payment via biometric authentication. Additional steps may be necessary if the user decides to use a card other than their default card or an app that doesn’t come pre-installed on their device.14

Even with such additional steps, tap-to-pay typically offers an easy and seamless mobile payment experience. Use of tap-to-pay at the POS has risen steadily in the U.S. as NFC technology has become more commonly included in both mobile devices and payment terminals.15 This rise is expected to continue—indeed, analysts estimate that the value of digital wallet tap-to-pay transactions will grow by over 150 percent by 2028.16

Figure 2: Forecast U.S. Total Digital Wallet NFC Transaction Value

Source: Juniper Research

The availability of different apps offering tap-to-pay varies depending on the type of mobile device. Below we examine the different approaches taken by the two dominant mobile device systems in the U.S.: the Apple ecosystem and Google’s Android ecosystem.

Apple and Google emerged relatively recently as significant players in the consumer payments space, where today they dominate the U.S. mobile tap-to-pay landscape. As two of the largest companies in the world, both could leverage their large networks of users and broad cross-section of existing products and services to gain market share in payments quickly.17

Both companies also use their mobile payments offerings to deepen customer engagement by keeping users on their platforms and increasing their use of the company’s full suite of services. The constant and instant access to user data and feedback that results from these customer relationships can allow companies to rapidly iterate on further product development, refinement, and delivery.18

Even with these underlying similarities, however, the two companies’ approaches to their mobile payments ecosystems diverge in important ways.

The Apple ecosystem

Apple uses a closed ecosystem, meaning that Apple manufactures all mobile devices in the system and provides the operating system (iOS) for these devices.19 Apple mobile devices come preloaded with the Apple Wallet app, a “digital wallet,” where users can load payment cards and other items.20 Users can then activate Apple Pay, Apple’s payment app, and start making tap-to-pay purchases, as well as online and in-app purchases (e.g., paying for an Uber ride).

Users can set one of the payment cards in their Apple Wallet as the default payment method, but they can also choose a particular payment method when making specific purchases. If a user has selected a certain credit card as the default method, for example, they can make tap-to-pay purchases by simply holding their phone near the merchant’s NFC terminal while using the phone’s built-in biometric authentication. And the user can switch to a non-default card instead by tapping the desired card from the list of options that pop up on the lock screen.

For a particular payment card to be available on Apple Pay, the card issuer must enter into a bilateral agreement with Apple. Currently, over 5,100 card issuers have such agreements with Apple.21 Under these agreements, Apple charges card issuers 0.15 percent on each credit transaction and a half a penny ($0.005) on each debit transaction.22 Apple also prohibits card issuers from directly passing the fees on to their cardholders.23 Apple does not publicly report the amount of revenue it derives from the transaction fees it charges card issuers, but analysts estimate that it was over $1.9 billion in 2022.24

While fees are one transparent way Apple monetizes Apple Pay, it also collects data through consumer use of the app, which may be used to develop new products or enhance its ability to market existing ones.25 For example, Apple is reportedly using consumer data, such as spending history and which devices a user owns, for its recently launched Buy Now, Pay Later service.26

Since Apple launched Apple Pay in the U.S. in October 2014,27 its use has steadily grown. Today, an estimated 130.1 million individuals use an iPhone at least once per month in the U.S.28 Roughly three in four U.S. iPhone users have activated Apple Pay.29 And an estimated 55.8 million U.S. consumers made an in-store payment using Apple Pay in April 2023, accounting for nearly half of iOS users.30

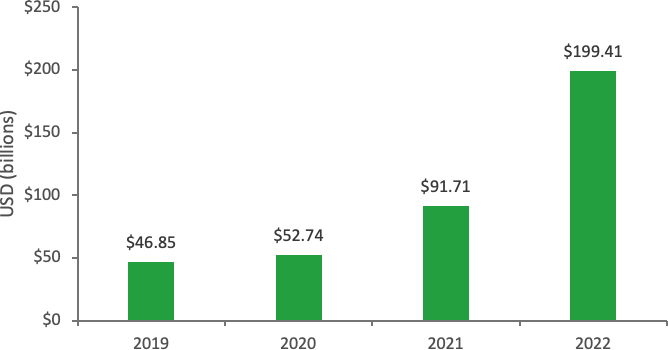

Analysts estimate that U.S. consumers spent $199 billion at stores using Apple Pay in 2022, up from $91.7 billion in 2021 and $46.9 billion in 2019.31

Figure 3: Estimated U.S. Consumer POS Spending Using Apple Pay

Source: PYMNTS.com

The Android ecosystem

In contrast, Google’s Android operating system32 can be used with mobile devices manufactured by other companies—e.g., Samsung and Motorola—not just the Pixel smartphones manufactured by Google itself. Over time, a number of payment apps have been available for making tap-to-pay purchases using Android devices, including other digital wallets (Samsung Pay,33 Softcard34) and specialty apps developed by other types of companies, such as banks (Capital One,35 Citibank,36 TD Bank,37 Barclays,38 BBVA39).

For consumers, digital wallets on Android devices, such as Google Pay and Samsung Pay, operate similarly to Apple Pay. Consumers load their payment cards and other payment methods into the wallet, set a default payment if they wish, and then use the device for tap-to-pay. For card issuers, however, Google Pay and Samsung Pay are different from Apple Pay. Card issuers pay zero transaction fees to the wallet provider when their card is used, and their relationship to the providers is governed largely by Visa and Mastercard network standards, rather than bilateral agreements.40 While Google does not charge a fee to issuers, it may be monetizing Google Pay through different means. Specifically, Google collects an immense amount of consumer data when consumers use the product.41 Google appears to use this data to develop new services and also in its advertisement business, among other things.42

In 2021, there were an estimated 25 million Google Pay users in the U.S., with expected growth of an additional 10.2 million users by 2025.43 In that same year, Samsung Pay had an estimated 16.3 million U.S. users, with users projected to grow by 2 million by 2025.44 Analysts estimate that U.S. consumers spent $65.2 billion at stores using Google Pay in 2022, up from $24.8 billion in 2021 and $39.89 billion in 2019.45 Samsung Pay accounted for $19.6 billion in U.S. sales in 2022, having followed a similar trend to Google Pay prior to 2021.46

Apple and Android market shares

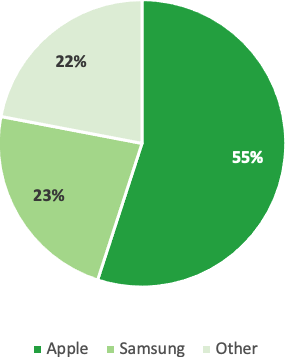

When it comes to mobile device operating systems, Apple’s iOS and Google’s Android OS are essentially the only two options, with iOS having a somewhat greater share than Android of the operating system market in the U.S.47 As a result, how the two firms design and offer their systems takes on outsized importance—they are the critical intermediaries that control access to an increasingly utilized payment option that will only gain importance as mobile device payments continue to grow.

Apple currently dominates the U.S. mobile device market by at least some measures. For instance, in Q2 2023, 55 percent of smartphones shipped in the U.S. were Apple devices. The next closest competitor (Samsung) accounted for 23 percent of smartphone shipments, and after that competitor shares dipped into the single digits.48

Figure 4: Share of U.S. Smartphone Shipments by Vendor (Q2 2023)

Data from Counterpoint Research

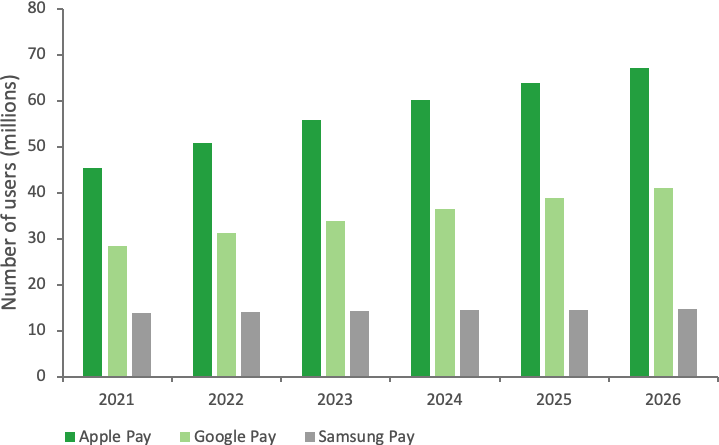

Apple also leads the market in U.S. digital wallet users, a trend that is expected to continue through 2026, according to a recent market survey.49 Mobile wallet adoption is being driven by younger consumers: in early 2023, 60 percent of consumers under the age of 40 had used a mobile wallet, while only 38 percent of consumers aged 40 or older had done the same.50 iPhone users also tend to skew younger than Android users.

Figure 5: Forecast U.S. Mobile Proximity Payment Users by Digital Wallet

Source: Insider Intelligence | eMarketer

Data from April 2023 survey measuring mobile phone users who made at least one proximity mobile payment transaction in the past six months using each respective platform.

QR code mobile payments

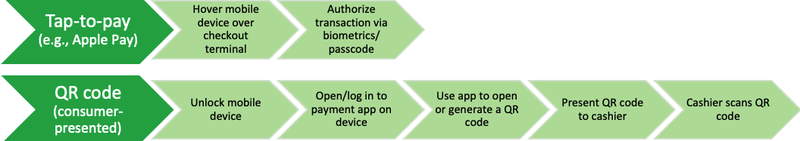

QR codes are another option for mobile device users to make payments at the POS, but QR code payments are comparatively less seamless than tap-to-pay.51 Payment apps that use QR codes generally function one of two ways—either the customer presents a QR code generated by the app to the merchant, or the customer uses the app to scan a QR code generated by the merchant’s POS terminal.52

Unlike many tap-to-pay transactions, QR code payments require extra steps—e.g., unlocking a mobile device, opening/logging in to an app, generating/scanning the code, confirming the payment. They also require a working camera and wireless connection. QR codes may also present greater security risk than NFC; while NFC cards send encrypted information unique to each payment, static QR codes provide the opportunity for fraudsters to intercept private details and redirect payments.53 Dynamic QR codes generated for specific transactions have made the modes more comparable, although the QR code payment is only a barcode that redirects users to a specified web address or application and therefore needs to be built with encryption in mind to be fully secure.54

Figure 6: Example Steps to Make POS Payments Using Tap-to-Pay vs. QR Code

POS payments using QR codes have continued to rise, owing at least in part to their low-tech nature—not all smartphones or merchant terminals have NFC chips, and QR codes require neither.55

Accessing NFC technology on Apple devices and Android devices

NFC access on Apple devices

As noted, Apple operates a hardware/software closed ecosystem: it both manufactures mobile devices and controls the iOS operating system for these devices. A developer of an app of any kind that wishes to make its app available on Apple devices needs access to the iOS operating system. Apple controls such access through various agreements and guidelines, including the Apple Developer Agreement.56 A developer of an app that involves NFC requires, in addition, access to the NFC chip on Apple devices. Apple controls such access through its Core NFC Guidelines.57 These Guidelines expressly deny such access for payment apps.58 Although payment apps other than Apply Pay can be downloaded to Apple devices via the Apple App Store, they are limited to offering QR codes or barcodes to allow users to make POS payments using an Apple device.59 They cannot be used for tap-to-pay on Apple devices, where the only option is Apple Pay.

NFC access on Android devices

No such NFC restriction policy currently exists for devices that use the Android OS, though Google could reverse this position in the future. Neither Android OS developer Google nor any of the Android mobile device manufacturers currently has a policy that restricts access to the NFC chip on these devices for payment apps.

Thus, users of Android devices are not limited to Google’s own payment app, Google Pay, when they want to make tap-to-pay payments using their device. As noted above, they have (or have had) several other payment app options, including other digital wallets (Samsung Pay, Softcard) and specialty apps developed by other types of companies, such as banks (Capital One, Citibank, TD Bank, Barclays, BBVA). Indeed, if Apple did not limit Apple Pay to its own devices, Android device users could be able to download Apple Pay.60

Market dynamics have entrenched Apple’s NFC policy

Card issuers have a financial incentive to prefer Android digital wallets, such as Google Pay and Samsung Pay, over Apple Pay: they have to pay transaction fees to Apple each time their card is used on Apple Pay, but no fees to the providers of Android digital wallets when their cards are used with such wallets.

But card issuers appear to have little, if any, leverage over Apple’s policies and practices. In 2015, Google was reportedly negotiating with large card issuers to impose transaction fees for use of their cards with Google Pay similar to the transaction fees charged by Apple. The negotiations were short-circuited when Visa and Mastercard changed their respective “tokenization” card-security service standard to prevent digital wallet providers from charging fees to card issuers when using the tokenization service.61 Prior to this change, Apple had negotiated bilateral agreements with card issuers, and has successfully resisted the attempt by the card networks and card issuers to impose this no-fee regime on Apple Pay.62

Apple device users are unlikely to influence Apple’s policy for a variety of reasons. First, a consumer’s choice of an Apple device over an Android device is based on numerous factors other than which tap-to-pay apps are available. That is, the variety of tap-to-pay apps on either device is not a significant driver of demand, and thus does not put meaningful competitive pressure on Apple’s policy. Second, even after a consumer selects either an Apple or Android device, switching from one ecosystem to the next is not costless. Even after entering the Apple ecosystem, if a consumer were to develop some preference for tap-to-pay alternatives, they are still unlikely to switch to an Android device given the switching costs. Finally, there is no guarantee that the current Android NFC access policy will remain in place.

Strategic rationales for Apple’s NFC policy

Some analysts have suggested that Apple’s NFC policy is driven by a strategy to address slowing iPhone sales by diversifying its revenue through its software and services.63 As the use of mobile device tap-to-pay continues to grow, the revenue stream from the transaction fees it charges card issuers (estimated at $1.9 billion in 2022) is expected to grow.64

Apple’s stated rationale for the policy is that it is needed to ensure privacy and security for Apple device users.65 In a 2016 filing responding to the Australian Competition & Consumer Commission, Apple explained that its secure payments are the result of a “tight integration of hardware, software, and services such as Apple Pay” and that allowing banks to access the NFC radio would undermine this security.66 The company argued that “Android devices, which provide open access to their NFC radios to banks, have been shown to be susceptible to third party attacks that can compromise the customer’s card information” and pointed to a 2016 report by Interpol that cited compromised card data on Android phones using NFC for payments.67

But Apple’s commitment to privacy and security does not necessarily conflict with open access to NFC for payments. Specifically, Apple could mandate that a third-party payment app seeking access to the NFC chip provide at least the same level of privacy as Apple Pay. This is the approach that Apple takes in other areas. For example, Apple restricts the apps users can install on their iOS devices to those available through Apple’s App Store, where apps must meet certain standards before they can be offered.68 And notably, Apple permits some access to NFC by app developers in limited circumstances—for example, “to give users more information about their physical environment and the real-world objects in it.”69

Potential strategic rationales for the open NFC access policy for Android devices

Google has generally taken a different approach to Android, which may contribute to its rationale for currently keeping NFC access open. Specifically, Google consistently advertises Android as being more open, for example by being open source, as a product differentiator to attract users.70 Google generates revenue by monetizing the data it collects from its users in its advertising business, among other ways. In fact, Google derives the overwhelmingly majority of its revenues from advertising, close to 80 percent in 2022.71 By contrast, Apple derived approximately 80 percent of its 2022 revenue by selling hardware.72

If Google began restricting access to various hardware, such as the NFC chip, it could undercut Android’s “open” image. In the past, though, Google has been fined billions of dollars by international authorities for imposing “illegal restrictions on Android device manufacturers” by requiring mobile device hardware companies to pre-install certain Google apps as a condition of using the Android OS.73 Given its dominant market position and relationship with hardware manufacturers, Google could reverse its open access NFC policy in the future if fee or data related considerations outweigh reputational or other risks.

Impacts of NFC access policies

In open banking, interoperability can generate substantial benefits for consumers by promoting choice and reducing barriers to entry for new firms.74 Given the growing use of contactless payments, hardware and software provider business decisions and models can have a significant impact on payment rails and the future of open banking. Policies that impose restrictions on competition and raise consumer switching costs must be carefully scrutinized.

Given the large share of Apple devices in the U.S. market, both existing NFC app providers and potential new entrants to the tap-to-pay sphere, such as banks, retailers, and established payment app providers (e.g., PayPal, Venmo, and Cash App) have a strong incentive to develop tap-to-pay apps for Apple devices. But Apple’s NFC restriction policy prevents them from doing so, and ultimately eliminates the possibility of consumer choice in tap-to-pay on Apple devices.

Indeed, the card issuers that have to pay transaction fees to Apple every time their card is used with Apple Pay have a financial incentive to create their own tap-to-pay apps for Apple devices. And even if a card issuer did not wish to develop its own tap-to-pay app, it would have an incentive to steer its cardholders to no-fee digital wallets such as Google Pay and Samsung Pay, and/or to threaten to pull their cards from Apple Pay. Taken together, such actions could exert competitive pressure on Apple to reduce or eliminate card issuer fees.

If additional tap-to-pay apps were available on Apple devices, Apple would have to compete head-to-head with the other app providers for Apple device users’ business. This could incentivize all of the providers to innovate, to develop new features and services that would keep their customers from switching to their competitors, attract their competitors’ customers, and attract new customers to their products instead of their competitors’ products.

The NFC access policy on Android devices provides a natural experiment that supports this analysis. Without restrictions like Apple’s, third-party apps have competed for space in the Android tap-to-pay ecosystem and offered various consumer-beneficial innovations and opportunities for consumer choice in the process.

For instance, in 2016, Barclays Bank introduced tap-to-pay through its Android app in the U.K. (adding to its existing list of wearable NFC payment devices, including a wristband, fob, and sticker).75 The Barclaycard app offered features not offered by either Google Pay or Samsung Pay, such as direct integration into the user’s banking app and all its functionality, including the ability to check account balances and transfer funds, as well as “instant card replacement” into the app in the event of a lost or stolen card.76 Similar innovative features were offered on other tap-to-pay Android apps that banks like Capital One and Citibank launched around the same time, providing an array of tap-to-pay options for consumers to choose on their Android devices.77 Banks did offer versions of their apps without tap-to-pay for iOS, but Apple device users would not have been able to benefit from the integrated features.78

Samsung Pay offered another innovation when it entered the market in 2015, a time when magnetic stripe cards and swipe-based merchant terminals were still widely used.79 The app came with another contactless payment feature alongside its NFC capabilities called Magnetic Secure Transmission, which mimicked a card swipe—but without requiring an actual swipe or any contact with the terminal. The feature allowed Samsung Pay to be used at older terminals without an NFC interface, benefitting both consumers and merchants with enhanced POS convenience at more locations than either Google Pay or Apple Pay.80

Another example comes from the addition of “host card emulation” (HCE) technology into the Android operating system in 2014, which made it easier for app developers to deploy NFC-based wallets.81 HCE allowed mobile apps to access payment card data from cloud storage instead of from phone hardware often controlled by mobile carriers. Before the shift, Google Pay didn’t support tap-to-pay “on the vast majority of phones running on Verizon, AT&T and T-Mobile,” a fact reportedly due at least in part to the three carriers backing Softcard, a competing wallet app.82 Reports at the time described a shift in the market following Google’s announcement about the new HCE integration: “Already…a number of mobile wallet providers have adopted the technique. Google Wallet is one, of course. Additionally, BBVA became the first bank to support HCE-enabled NFC payments via its mobile wallet…Mastercard also collaborated with Capital One to pilot an HCE-enabled mobile wallet.”83

The Apple “map” app serves as a useful illustration of the potential benefits of increased competition. Apple initially contracted with Google to install Google Maps as the default map on its first series of iPhones. But in 2012, Apple dropped the contract and launched its own navigation app called Maps.84 The new app was universally panned at first—there were even reports of “potentially life threatening” navigation flaws85—but Apple worked to improve Maps to compete with Google Maps.86 There is also evidence that over the years, Google updated features of Google Maps in response to Maps updates.87 Today, users benefit from public transit directions, 3-D flyover views, and in-app recommendations in both apps.88

Concerns about the potential anticompetitive effects of Apple’s NFC restriction policy have been raised in legal challenges both in the U.S. and abroad.89 In 2017, the Australian Competition & Consumer Commission assessed the harms and benefits of Apple’s policy in denying a challenge to the policy brought by several banks.90 In May 2022, the European Commission charged Apple with abusing its dominant position in markets for mobile wallets on iOS devices by preventing developers from accessing necessary NFC technology “to the benefit of its own solution, Apple Pay.”91 And in July 2022, Apple was sued in a California federal district court by payment card issuers alleging that Apple’s policy violates U.S. antitrust laws.92

Promoting competitive markets for mobile payments

Consumers, honest businesses, and the entire economy benefit when consumer finance markets are open and fiercely competitive, characterized by decentralized market power of market participants, interoperability, low switching costs, and limited incumbency advantages, among others. The CFPB is committed to ensuring that consumer finance markets are markets where consumers have choices, the best products win, and large incumbents cannot stifle competition by exploiting their network effects or market power.

As the use of mobile devices at the POS continues to grow in the U.S., the companies controlling mobile device operating systems and hardware will remain critical intermediaries in the mobile payments ecosystem. And the two dominant players in this space, Apple and Google, will likely retain an outsized impact on consumers’ access to and use of various mobile payment solutions. This has significant implications for open banking, including with respect to interoperability. For instance, any frictions either company imposes on access to essential hardware or software could impede the shift towards open banking and, ultimately, negatively impact consumers—e.g., by reducing competition, innovation, choice, and ease of access.

Accordingly, as the CFPB and other jurisdictions build out open banking and finance frameworks, we will continue to assess roadblocks to open ecosystems that drive competition and promote consumer benefits. On open banking and payments, there is broad interest from consumer protection, privacy and data protection, and financial regulators in jurisdictions around the world. The CFPB will continue to work with these entities and take appropriate steps to ensure that Big Tech companies do not impede the development of open ecosystems for digital payments.

Footnotes

- This issue spotlight is not intended to impose any obligations or define any rights and is not intended as a CFPB interpretation of any regulation or statute.

- See Thomas Durkin, Credit Cards: Use and Consumer Attitudes, 1970-2000, Fed. Rsrv. Bull. (Sept. 2000), https://www.federalreserve.gov/pubs/bulletin/2000/0900lead.pdf .

- See Kevin Foster, Claire Greene, & Joanna Stavins, The 2021 Survey and Diary of Consumer Payment Choice: Summary Results, Working Paper No. 22-2, Fed. Rsrv. Bank of Atlanta (2022), https://www.atlantafed.org/-/media/documents/banking/consumer-payments/survey-diary-consumer-payment-choice/2021/sdcpc_2021_report.pdf .

- See Durkin, supra note 2.

- The U.S. was one of the last countries in the world to adopt EMV cards. While the technology was available in Europe starting in 1994 and encompassed more than 80 percent of European card transactions by 2015, American businesses were reluctant to update due to the high costs of reissuing cards and replacing terminals. Adoption only picked up steam after the card networks set a 2015 deadline for shifting fraud liability to the party (issuer or merchant) that had not switched to chip cards. See Patricia Moloney Figiola, Cong. Rsch. Serv., R43925, The EMV Chip Card Transition: Background, Status, and Issues for Congress, CRS Report R43925, Cong. Rsch. Serv. (2016), https://sgp.fas.org/crs/misc/R43925.pdf .

- Alex Rolfe, US Market Hits 1 Billion EMV Chip Cards Milestone, Payments Cards & Mobile (June 1, 2020), https://www.paymentscardsandmobile.com/us-market-hits-1-billion-emv-chip-cards-milestone/ ; see also Tom Philips, More Than 90% of Card Present Payments Worldwide Were Made Using EMV Chip Cards in 2021, NFC World (June 13, 2022), https://www.nfcw.com/2022/06/13/377453/more-than-90-of-card-present-payments-worldwide-were-made-using-emv-chip-cards-in-2021 .

- Coming Soon: Make Your Phone Your Wallet, Google (May 26, 2011), https://googleblog.blogspot.com/2011/05/coming-soon-make-your-phone-your-wallet.html ; Apple Pay Set to Transform Mobile Payments Starting October 20, Apple (Oct. 16, 2014), https://www.apple.com/newsroom/2014/10/16Apple-Pay-Set-to-Transform-Mobile-Payments-Starting-October-20/ .

- Cameron Faulkner, What Is NFC? Everything You Need to Know, techradar (May 9, 2017), https://www.techradar.com/news/what-is-nfc .

- See Dan Sanford, Contactless in the U.S.: Tapping into the Future of Payments, Visa Navigate, https://navigate.visa.com/na/spending-insights/tapping-into-the-future-of-payments (last updated Apr. 2021). Contactless cards came late to the U.S. market compared to other countries like the U.K., which “introduced contactless payments on its public transport system in 2014.” Elizabeth Schulze, Contactless Cards are Just Catching on in the US — Years After the Rest of the World, CNBC (Apr. 12, 2019), https://www.cnbc.com/2019/04/12/contactless-cards-and-apple-pay-are-just-catching-on-in-the-us.html .

- Mobile and Digital Wallets: U.S. Landscape and Strategic Considerations for Merchants and Financial Institutions, U.S. Payments Forum, at 5 (Jan. 2018), https://www.uspaymentsforum.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/Mobile-Digital-Wallets-WP-FINAL-January-2018.pdf .

- Caitlin Mullen, Will Biometrics be the Future of Payments?, Payments Dive (Sept. 26, 2022), https://www.paymentsdive.com/news/biometrics-future-payments-amazon-mastercard-fido-alliance-palm-pay-face-authentication/631882/ .

- See Chantal Tode, Starbucks Reaches 42M Mobile Payment Transactions as App Gains Momentum, RetailDive (2017), https://www.retaildive.com/ex/mobilecommercedaily/starbucks-reaches-42m-mobile-payment-transactions-as-app-gains-momentum .

- See J.D. Biersdorfer, Cracking Quick Response Codes with iOS 11, N.Y. Times (Dec. 18, 2017), https://www.nytimes.com/2017/12/18/technology/personaltech/cracking-quick-response-codes-with-ios-11.html .

- Additional steps for apps that are not pre-installed could include, for instance, downloading the desired app, unlocking the phone, opening the app, logging into the app, and navigating to the tap-to-pay feature.

- See David Huen, NFC or QR Codes? Both Have a Path Forward in Mobile Payments, Am. Banker (May 3, 2021), https://www.americanbanker.com/news/nfc-or-qr-codes-both-have-a-path-forward-in-mobile-payments .

- Digital Wallets: Platform Analysis, Key Trends and Market Forecasts 2023-2028, Juniper Res. (Oct. 2023), https://www.juniperresearch.com/researchstore/fintech-payments/digital-wallet-research-report .

- Paul Tierno, Big Tech in Financial Services, CRS Report R47104, Cong. Rsch. Serv., at 23 (updated July 29, 2022), https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/R/R47104 ; Report to the White House Competition Council: Assessing the Impact of New Entrant Non-bank Firms on Competition in Consumer Finance Markets, Dep’t of the Treas., at 92-98 (Nov. 2022), https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/136/Assessing-the-Impact-of-New-Entrant-Nonbank-Firms.pdf .

- Id.

- Michael Goad & Colin Steele, Definition: Mobile Operating System, TechTarget (last updated Mar. 2023), https://www.techtarget.com/searchmobilecomputing/definition/mobile-operating-system .

- As of August 1, 2023, users could load debit or credit cards, transit cards, rewards cards, boarding passes, events tickets, digital keys, ID cards, and Apple Cash accounts into Apple Wallet. See Keep Cards and Passes in Wallet on iPhone, Apple, https://support.apple.com/guide/iphone/keep-cards-and-passes-in-wallet-iphc05dba539/16.0/ios/16.0 (last visited Aug. 2, 2023); Use Apple Pay for Contactless Payments on iPhone, Apple, https://support.apple.com/guide/iphone/use-apple-pay-for-contactless-payments-iphbd4cf42b4/ios (last visited Aug. 2, 2023).

- See Apple Pay Participating Banks in Canada, Latin, America, and the United States, Apple, https://support.apple.com/en-us/HT204916 (last visited July 20, 2023).

- See Alistair Barr & Robin Sidel, Google Misses Out on Apple’s Slice of Mobile Transactions, Wall St. J. (updated June 5, 2015), https://www.wsj.com/articles/google-loses-key-mobile-payment-feesgoogle-misses-out-on-apples-slice-of-mobile-transactions-1433546638 ; Defendant Apple Inc.’s Motion to Dismiss Amended Class Action Complaint at 4, Affinity Credit Union v. Apple Inc., No. 4:22-cv-04174 (N.D. Ca. Nov. 23, 2022).

- See Defendant Apple Inc.’s Motion to Dismiss Amended Class Action Complaint at 4, Affinity Credit Union v. Apple Inc., No. 4:22-cv-04174 (N.D. Ca. Nov. 23, 2022). “Such Corporate Client shall be prohibited from passing fees attributable to Apple Pay on to individual Cardholders or individuals authorized to use any Cards issued to Corporate Client.” Apple Payment Platform Program Manager Customer Terms and Conditions, Stripe (Dec. 1, 2022), https://stripe.com/legal/issuing/celtic/apple-payment-platform-program-manager-customer-terms-and-conditions .

- See Mark Gurman, Apple Keeps Its Tap-to-Pay Feature to Itself to Protect Revenue, Bloomberg (May 8, 2022), https://www.bloomberg.com/news/newsletters/2022-05-08/can-third-party-banks-and-apps-use-apple-aapl-iphone-nfc-for-tap-to-pay-l2xckg5e ; Telis Demos & Dan Gallagher, Apple Pay’s Long Road to Paying Off Is Getting Shorter, Wall St. J. (Apr. 21, 2023), https://www.wsj.com/articles/apple-pays-long-road-to-paying-off-is-getting-shorter-7a179c75 .

- Apple Pay Security and Privacy Overview, Apple (May 10, 2023), https://support.apple.com/en-us/HT203027 (“And when you use Apple Pay with credit, debit, or prepaid cards, Apple doesn’t retain any transaction information that can be tied back to you. Your transactions stay between you, the merchant or developer, and your bank or card issuer. . . . Apple retains anonymous transaction information, including the approximate purchase amount, app developer and app name, approximate date and time, and whether the transaction completed successfully.”).

- Mark Gurman, Apple to Scrutinize Customer History for New ‘Buy Now, Pay Later’ Service, Bloomberg (Feb. 14, 2023), https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2023-02-15/apple-to-scrutinize-customer-history-for-new-apple-pay-later-service (“The Apple Pay Later service . . . will evaluate borrowers based on their spending history and even which of the company’s devices they own.”).

- Apple, supra note 7.

- See Insider Intelligence, Smartphone Users, by OS, eMarketer (Mar. 2023), https://forecasts-na1.emarketer.com/584b26021403070290f93a22/5851918b0626310a2c186ae7 .

- Ben Cohen, Wait, When Did Everyone Start Using Apple Pay?, Wall St. J. (Aug. 18, 2022), https://www.wsj.com/articles/apple-pay-iphone-wallet-apps-11660780139 (citing data from Loup Ventures).

- Insider Intelligence, Apple Pay Users and Penetration, eMarketer (Apr. 2023), https://forecasts-na1.emarketer.com/602abc737351f403b84c00a2/5efc3dbf83c627071411ab7f .

- Apple Pay Has 48% Share of Mobile Wallets Yet Only Tiny Sliver of Total Retail Payments, PYMNTS (Aug. 15, 2022), https://www.pymnts.com/mobile-wallets/2022/apple-has-dominant-48-share-of-mobile-wallets-but-only-tiny-slice-of-total-retail-payments/ .

- The Android operating system was first developed by Android Inc. but was acquired by Google in 2005. After further development of the system, the first commercially available Android device, the HTC Dream, hit the marketplace in September 2008. See Oliver Cragg, Remembering the First Android Phone, the T-Mobile G1 (HTC Dream), Android Auth. (Sept. 24, 2021), https://www.androidauthority.com/first-android-phone-t-mobile-g1-htc-dream-906362/ . Today, anyone can access and use the Android source code through the Android Open Source Project. See Frequently Asked Questions, Android Open Source Project (last updated Feb. 2, 2023), https://source.android.com/docs/setup/about/faqs . This open-source format allows third-party software and app developers to use the Android source code and technology to develop their own products. See Contributing, Android Source Code, https://source.android.com/docs/setup/contribute (last visited Aug. 7, 2023). That said, there is some debate about the extent to which the Android operating system has consistently been truly open. See, e.g., Euro. Union Judgment of the General Court, Google v. Euro. Comm’n, T-604/18, para. 223-234 (Sept. 14, 2022), https://curia.europa.eu/juris/document/document.jsf?text=&docid=265421&pageIndex=0&doclang=EN ; Ron Amadeo, Google’s Iron Grip on Android: Controlling Open Source by Any Means Necessary, Ars Technica (July 21, 2018), https://arstechnica.com/gadgets/2018/07/googles-iron-grip-on-android-controlling-open-source-by-any-means-necessary/ . For instance, device manufacturers that want to include Google’s proprietary apps (e.g., Google Play, Gmail, YouTube, Google Maps) on their Android devices must meet certain compatibility requirements and obtain licenses from Google. See Android Compatibility Program Overview, Android Open Source Project (last updated Aug. 2, 2022), https://source.android.com/docs/compatibility/overview .

- Note that Samsung launched Samsung Wallet in the U.S. in June 2022 as a replacement for Samsung Pay. The new app is not available on non-Samsung phones. See Introducing Samsung Wallet: An Easy-To-Use, Secure Platform that Holds Everything Your Digital Life Needs, Samsung Mobile Press (June 16, 2022), https://www.samsungmobilepress.com/press-releases/introducing-samsung-wallet-an-easy-to-use-secure-platform-that-holds-everything-your-digital-life-needs . “You cannot install the [Samsung Pay] app from the Google Play Store now and the service doesn’t work even if you already have the app installed.” Ankit Banerjee, How to Set Up and Use Samsung Wallet (Samsung Pay), Android Auth. (June 23, 2023), https://www.androidauthority.com/setup-use-samsung-wallet-pay-3223698/ .

- In 2013, three phone carriers—Verizon, AT&T, and T-Mobile—jointly offered the Softcard mobile wallet, which used NFC technology to allow device owners to make tap-to-pay payments using their phones. See Roger Cheng, Isis Mobile Wallet Goes Live Nationwide, Offers Freebies, CNET (Nov. 14, 2013), https://www.cnet.com/tech/mobile/isis-mobile-wallet-goes-live-nationwide-offers-freebies/ . The carriers originally blocked Google Wallet from devices sold on their networks, ostensibly to push the Softcard app, but “Softcard never gained much traction with consumers, and now Apple Pay is threatening to eat everyone’s lunch.” Neil McAllister, Google Deal Means Game Over for Mobile Payments Firm Softcard, The Reg. (Feb. 25, 2015), https://www.theregister.com/2015/02/25/softcard_shutdown/ . In 2015, Google acquired Softcard’s technology, and the three carriers began loading the Google Wallet app onto their Android smartphones. See Roger Cheng, Google Wallet, Softcard Partner to Take on Apple Pay, CNET (Feb. 23, 2015), https://www.cnet.com/tech/mobile/google-wallet-softcard-partner-on-mobile-payments/ .

- In 2015, Capital One became the first U.S. bank to offer tap-to-pay functionality through its existing wallet app. Jason Del Rey, The Next Big Competitors for Android Pay and Samsung Pay: Banks, Vox (Oct. 16, 2015), https://www.vox.com/2015/10/16/11619664/the-next-big-competitors-for-android-pay-and-samsung-pay-banks . As of June 12, 2018, the Capital One Wallet app was removed from the major app stores. The Capital One Wallet App is Transitioning to a Whole New Form, AppAdvice (June 12, 2018), https://appadvice.com/app/capital-one-wallet/907210949 .

- Citi Unveils Global Digital Wallet: Citi Pay, Citibank (Nov. 10, 2016), https://www.citigroup.com/global/news/press-release/2016/citi-unveils-global-digital-wallet-citi-pay ; Citi Pay Launches in the U.S., Citibank (July 6, 2017), https://www.citigroup.com/global/news/press-release/2017/citi-pay-launches-in-the-us . As of August 31, 2019, Citi stopped offering its payment app. William Charles, Citi Pay Masterpass to Be Discontinued on August 31st, 2019, Dr. of Credit (July 30, 2019), https://www.doctorofcredit.com/citi-pay-masterpass-to-be-discontinued-on-august-31st-2019/ .

- Rian Boden, TD Canada Trust Launches NFC Mobile Payments with Support From All Three Major Carriers, NFC World (May 15, 2014), https://www.nfcw.com/2014/05/15/329169/td-canada-trust-launches-nfc-mobile-payments-support-three-major-carriers/ . As of November 1, 2022, TD Bank stopped offering mobile payment functionality on its app. Jonathan Lamont, TD App’s Mobile Payment to Shut Down November 1, MobileSyrup (Oct. 31, 2022), https://mobilesyrup.com/2022/10/31/td-app-mobile-payment-shutdown-november-1/ (“TD cited the ‘growing popularity of other digital wallets’ for the shutdown of Mobile Payment.”).

- Barclays began offering tap-to-pay payments to U.K. consumers through its Barclaycard Android app in January 2016. Nick Summers, Barclaycard Brings NFC Payments to its Android App, Engadget (Jan. 15, 2016), https://www.engadget.com/2016-01-15-barclaycard-android-nfc-payments.html (“Android Pay still isn't available in the UK, so Barclays has decided to fill the void with its own NFC-enabled contactless payments.”). Several months later, it added its credit and debit cards to Apple Pay for U.K.-based customers but said it “had no plans to join Android Pay or Samsung Pay” and noted that customers could already use the Barclaycard app to make tap-to-pay payments on Android devices. Leo Kelion, Barclays Bank Joins Apple Pay in UK, BBC (Apr. 5, 2016), https://www.bbc.com/news/technology-35968102 . As of June 30, 2023, Barclays stopped offering tap-to-pay through its own app. Barclaycard App Terms and Conditions, Barclays (Apr. 2023), https://www.barclays.co.uk/ways-to-bank/mobile-banking-app/april-2023-terms-conditions/ .

- Verdict Staff, BBVA, Visa Roll Out Solution for Cloud-Based Mobile Payments, Elec. Payments Int’l (July 1, 2014), https://www.electronicpaymentsinternational.com/news/bbva-visa-roll-out-solution-for-cloud-based-mobile-payments-010714-4307097/ . BBVA now offers tap-to-pay through Google Pay, Samsung Pay, and Apple Pay. How To Make Mobile Payments, BBVA, https://www.bbva.es/en/personas/banca-online/como-pago-desde-movil.html (last visited July 14, 2023).

- See AnnaMaria Andriotis, Apple Pay Fees Vex Credit-Card Issuers, Wall St. J. (Oct. 5, 2021), https://www.wsj.com/articles/apple-pay-fees-vex-credit-card-issuers-11633449317 ; Barr, supra note 22.

- Google Payments Privacy Notice, Google (last modified Mar. 28, 2022), https://payments.google.com/payments/apis-secure/get_legal_document?ldo=0&ldt=privacynotice&ldl=en (“When you use Google Payments to conduct a transaction, we may collect information about the transaction, including the date, time and amount of the transaction, the merchant's location and description, a description provided by the seller of the goods or services purchased, any photo that you choose to associate with the transaction, the names and email addresses of the seller and buyer (or sender and recipient), the type of payment method used, your description of the reason for the transaction and the offer associated with the transaction, if any.”).

- Id. (“[I]f you do not want our affiliates to use your personal information collected by us and shared with them to market to you . . . please indicate your preference.”); see also Google Privacy Policy, Google (effective July 1, 2023), https://policies.google.com/privacy?hl=en-US (identifying one use of collected date to “[p]rovide personalized services, including content and ads”).

- See Sarah Perez, Fueled by Pandemic, Contactless Mobile Payments to Surpass Half of all Smartphone Users in U.S. by 2025, Tech Crunch (Apr. 5, 2021), https://techcrunch.com/2021/04/05/fueled-by-pandemic-contactless-mobile-payments-to-surpass-half-of-all-smartphone-users-in-u-s-by-2025/ .

- Id.

- See PYMNTS, supra note 31.

- Id.

- Measured by U.S. shipments of smartphones with one or the other operating system loaded, Apple currently has 52 percent of the market, and Android has 48 percent. See Global Smartphone Sales Share by Operating System, Counterpoint (Aug. 30, 2023), https://www.counterpointresearch.com/insights/global-smartphone-os-market-share/ . Note that smartphone shipments are not necessarily the only way to measure operating system market shares.

- See US Smartphone Shipments Market Data (Q1 2022 – Q2 2023), Counterpoint (Aug. 17, 2023), https://www.counterpointresearch.com/us-market-smartphone-share/ . Note that smartphone shipments are not necessarily the only way to measure mobile device market shares.

- See Insider Intelligence, Proximity Mobile Payment Users, by Platform, eMarketer (Apr. 2023), https://forecasts-na1.emarketer.com/584b26021403070290f93a28/5aea079ba2835f033cca36be .

- Banking and Payments Intelligence Report, J.D. Power (Jan. 24, 2023), https://www.jdpower.com/business/resources/mobile-wallets-gain-popularity-growing-number-americans-still-prefer-convenience .

- “‘With NFC, you just tap without having to put your thumb in a certain place for the reader to accept it, and it gives it the edge in contactless transit and in-store for that reason,’ [Nick Starai, chief technology officer at payment gateway company NMI] said. ‘With QR codes, you have to open the phone to connect with an image and the phone has to be in the right position for it to work.’” Huen, supra note 15. “[T]he readability between the consumer’s QR code, and the QR code reader can be limiting. Even when viewing this authorization process in its most basic form, the QR code must be visually presented, aligned within a suitable range, scanned and approved, taking precious time. . . . This is in contrast to a contactless chip-based ticket, usually enabled by NFC technology, which only needs to be within a predefined range of the turnstile/terminal to be validated and is unrivaled in providing validations quickly and successfully.” Philippe Vappereau, QR Codes Are Helpful, But Ticketing Needs a Better Option, Am. Banker (May 10, 2021), https://www.americanbanker.com/payments/opinion/qr-codes-are-helpful-but-ticketing-needs-a-better-option .

- U.S. Payments Forum, supra note 10, at 17-18.

- “For consumers, a big risk comes from fake QR codes in a seemingly legitimate setting, which can download malicious software, execute phishing scams or make fraudulent payments.” Vappereau, supra note 51.

- Terri Bradford, Fumiko Hayashi, & Ying Lei Toh, Developments of QR Code-Based Mobile Payments in East Asia, Fed. Rsrv. Bank of Kansas City (June 2019), https://www.kansascityfed.org/Payments%20Systems%20Research%20Briefings/documents/7599/psr-briefingjun2019.pdf ; Tanya Candia, QR Code Security: Why They Are the Next Cybersecurity Battlefield, BizTech (Nov. 18, 2022), https://biztechmagazine.com/article/2022/11/why-qr-codes-are-next-cybersecurity-battlefield .

- “In other parts of the world, fragmentation in payments is more prominent, leading to a variety of payment instruments and methods and varying systems within the banks. . . . ‘That is why a QR code is a quicker payment method when you have no infrastructure or rails to handle card payments and contactless technology.’” Huen, supra note 15 (quoting Nick Starai, chief technology officer at NMI); see also David Huen, Why Entering a Contactless World is No Easy Task for Merchants, Am. Banker (Oct. 14, 2020), https://www.americanbanker.com/payments/news/why-entering-a-contactless-world-is-no-easy-task-for-merchants .

- Agreements and Guidelines for Apple Developers, Apple, https://developer.apple.com/support/terms/ (last visited July 14, 2023).

- Core NFC, Apple, https://developer.apple.com/documentation/corenfc (last visited Sept. 6, 2023).

- “Important: Core NFC doesn’t support payment-related Application IDs.” Id.

- For example, the Chase Pay iOS app used QR codes for POS payments before it was ultimately discontinued in 2020. This use of QR codes reportedly contributed to the app’s limited adoption. “Chase Pay could not access the NFC chip on Apple Inc.’s popular iPhone and thus ‘was forced to use a QR code interface, which requires merchant support, and apparently they were not successful in getting enough of that.’” Jim Daly, Chase to Discontinue Chase Pay Mobile App Early Next Year; Online and In-App Functions to Remain, Digit. Transactions (Aug. 21, 2019), https://www.digitaltransactions.net/chase-to-discontinue-chase-pay-mobile-app-early-next-year-online-and-in-app-functions-to-remain/ (quoting Aaron McPherson, vice president for research operations at Mercator Advisory Group Inc.).

- See Devices Compatible with Apple Pay, Apple (May 9, 2023), https://support.apple.com/en-us/HT208531 .

- See Barr, supra note 22.

- “Some big banks previously tried to get their Apple Pay fees lowered around 2017 but didn’t succeed, according to people familiar with the matter.” Andriotis, supra note 40. “[E]xpert observers and financial-institution executives argue most if not all of the early signees are likely to re-up or have already done so, despite financial terms many experts consider unusual if not onerous.” John Stewart, Apple Pay: Can’t Get Along with It, Can’t Get Along Without It, Digit. Transactions (Oct. 31, 2017), https://www.digitaltransactions.net/magazine_articles/apple-pay-cant-get-along-with-it-cant-get-along-without-it/ .

- See Tripp Mickle, Apple’s iPhone Powers Growth, but Signs Point to a Slowdown, N.Y. Times (Oct. 27, 2022), https://www.nytimes.com/2022/10/27/technology/apple-aapl-iphone-q4-earnings.html ; Stefan Modrich, Tracking Apple’s Growing Fintech Ambitions, S&P Glob. (Nov. 22, 2022), https://www.spglobal.com/marketintelligence/en/news-insights/latest-news-headlines/tracking-apple-s-growing-fintech-ambitions-72910844 .

- See Gurman, supra note 24; Telis Demos & Dan Gallagher, Apple Pay’s Long Road to Paying Off Is Getting Shorter, Wall St. J. (Apr. 21, 2023), https://www.wsj.com/articles/apple-pays-long-road-to-paying-off-is-getting-shorter-7a179c75 .

- See Gurman, supra note 24.

- Submission by Apple, Authorisation Applications A91546 & A91547, Austl. Competition & Consumer Comm’n, at 11 (Aug. 26, 2016), https://www.accc.gov.au/system/files/public-registers/documents/D16%2B118859.pdf .

- Id., at 11. “The possibility of compromising NFC transactions was explored by academia years ago and it appears that fraudsters have finally made progress in the area. Several vendors in the Darknet offer software that uploads compromised card data onto Android phones in order to make payments at any stores accepting NFC payments.” Internet Organized Crime Threat Assessment (IOCTA) 2016, Europol, at 30 (2016), https://www.europol.europa.eu/cms/sites/default/files/documents/europol_iocta_web_2016.pdf .

- See, e.g., Apple Platform Security: Intro to App Security for iOS and iPadOS, Apple (Feb. 18, 2021), https://support.apple.com/guide/security/intro-to-app-security-for-ios-and-ipados-secf49cad4db/1/web/1 .

- Core NFC, Apple, https://developer.apple.com/documentation/corenfc (last visited July 19, 2023). Another example: Apple launched a new service last year that permits merchants to use their iPhones’ NFC technology to accept tap-to-pay payments of any type—i.e., not only payments using Apple Pay, but also chip-enabled cards, and even Android devices—without the need for additional hardware or payment terminals. Apple Empowers Businesses to Accept Contactless Payments Through Tap to Pay on iPhone, Apple (Feb. 8, 2022), https://www.apple.com/newsroom/2022/02/apple-unveils-contactless-payments-via-tap-to-pay-on-iphone/ (“Tap to Pay on iPhone will be available for payment platforms and app developers to integrate into their iOS apps and offer as a payment option to their business customers.”); see also Square, Tap to Pay on iPhone, https://squareup.com/us/en/payments/tap-to-pay (last visited Sept. 5, 2023) (“Tap to Pay on iPhone uses the built-in features of iPhone to keep your business and your customer data private and secure. When a payment is processed, Apple does not store card numbers on the device or on Apple servers, so you can rest assured knowing your business stays yours.”).

- See, e.g., Android is for Everyone, Android, https://www.android.com/everyone/ (last visited Sept. 1, 2023) (“Android’s open platform helps people around the globe enjoy greater access to more information and opportunity than ever before”).

- Alphabet Inc., Annual Report (Form 10-K) (Feb. 3, 2023).

- Apple Inc., Annual Report (Form 10-K) (Sept. 24, 2022).

- Some jurisdictions have already found Google has not always lived up to its claims of an open Android ecosystem. See, e.g., Antitrust: Commission Fines Google €4.34 Billion for Illegal Practices Regarding Android Mobile Devices to Strengthen Dominance of Google's Search Engine, Eur. Comm’n (July 18, 2018), https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/IP_18_4581 (“Our case is about three types of restrictions that Google has imposed on Android device manufacturers and network operators to ensure that traffic on Android devices goes to the Google search engine. In this way, Google has used Android as a vehicle to cement the dominance of its search engine. These practices have denied rivals the chance to innovate and compete on the merits. They have denied European consumers the benefits of effective competition in the important mobile sphere. This is illegal under EU antitrust rules.”) (quoting Commissioner Margrethe Vestager, in charge of competition policy at the European Commission).

- For digital systems, the term “interoperability” refers to “the ability of technical systems to exchange data seamlessly and interactively. . . . Interoperability can make it possible for new entrants to innovate upon existing technologies. . . . [I]nteroperability has the potential to address lock-in due to network effects. . . . While many digital platforms benefit from network effects, they can lead markets to tip to a single firm. Later entrants have a hard time breaking into the market, even if they offer higher quality services, because customers are effectively locked into their current platform choices. Interoperability between platforms helps to reduce this lock-in by allowing new platforms to enter the market and compete for customers with higher quality and more innovative products.” Sukhi Gulati-Gilbert & Robert Seamans, Data Portability and Interoperability: A Primer on Two Policy Tools for Regulation of Digitized Industries, Brookings (May 9, 2023), https://www.brookings.edu/articles/data-portability-and-interoperability-a-primer-on-two-policy-tools-for-regulation-of-digitized-industries-2/

- Summers, supra note 38; Matt Brian, Barclaycard Steps Up its Contactless Game with Three New NFC Devices, Engadget (June 29, 2015), https://www.engadget.com/2015-06-29-barclaycard-bpay-nfc-devices.html . As noted above, Barclays stopped offering this functionality in June 2023. See supra note 38. Currently, iOS device users can add a Barclay card to Apple Pay and/or download the Barclays app to their iPhones, but they cannot make NFC-enabled payments through the Barclays app itself.

- See Contactless Mobile, Barclays, https://www.barclays.co.uk/ways-to-bank/mobile-banking-services/contactless-mobile/ (last visited July 19, 2023); James Rigg, Barclaycard to Launch NFC Payments on Android Ahead of Apple Pay, Engadget (Sept. 15, 2015), https://www.engadget.com/2015-09-15-barclaycard-nfc-payments-android.html .

- See supra notes 35-39.

- For a while, Barclays was an outlier in the U.K. in that it did not support Apple Pay, which meant Apple device users had no avenue to use a Barclays card to make tap-to-pay payments at all. Summers, supra note 38.

- Samsung Announces Launch Dates for Groundbreaking Mobile Payment Service: Samsung Pay, Samsung Newsroom (Aug. 14, 2015), https://news.samsung.com/global/samsung-announces-launch-dates-for-groundbreaking-mobile-payment-service-samsung-pay .

- See Nadeem Sarwar, Why Samsung Pay App on Some Galaxy Phones Is Better Than Other Tap-To-Pay Apps, SlashGear (Jan. 17, 2023), https://www.slashgear.com/1169320/why-samsung-pay-app-on-some-galaxy-phones-is-better-than-other-tap-to-pay-apps/ . Beginning in 2021, Samsung phased out MST technology from new phone models in the U.S., in part due to the increased use of NFC terminals and declining importance of magnetic stripes. Id.

- See John Heggestuen, What The Newest Mobile Payments Tech, ‘Host Card Emulation,’ Means For The Industry, Insider (July 30, 2014), https://www.businessinsider.com/host-card-emulation-doesnt-overcome-most-important-problem-in-payments-2014-7 .

- Jason Del Rey, How MasterCard and Visa Just Made Banks the Next Big Players in Mobile Payments, Vox (Feb. 19, 2014), https://www.vox.com/2014/2/19/11623632/how-your-banks-app-may-someday-replace-your-wallet-thanks-to .

- Heggestuen, supra note 81.

- Darrell Etherington, Apple Reportedly Ditched Google Maps Over Lack of Turn-by-Turn Navigation, Tech Crunch (Sept. 26, 2012), https://techcrunch.com/2012/09/26/apple-reportedly-ditched-google-maps-over-lack-of-turn-by-turn-navigation/ .

- See Ian Sherr, Apple Makes a Wrong Turn as Users Blast Map Switch, Wall St. J. (updated Sept. 28, 2012), https://www.wsj.com/articles/SB10000872396390443890304578008712527187512 ; Ann-Marie Alcántara, People Have Begun to Love Apple’s Most Hated Product, Wall St. J. (July 17, 2023), https://www.wsj.com/articles/apple-maps-app-popularity-iphone-8e52aec1 .

- Some consumers are reportedly beginning to choose Maps over Google Maps for its clean interface and integration with CarPlay. Ben Lovejoy, Apple Maps Versus Google Maps: Tide is Turning, Say Analysts, 9to5Mac (July 18, 2023), https://9to5mac.com/2023/07/18/apple-maps-versus-google-maps/ ; see also How Many People Use Google Maps Compared to Apple Maps?, justinobeirne.com (July 2021) https://www.justinobeirne.com/how-many-people-use-google-maps-compared-to-apple-maps (last visited July 31, 2023).

- See, e.g., A Year of Google & Apple Maps, justinobeirne.com (2017), https://www.justinobeirne.com/a-year-of-google-maps-and-apple-maps (last visited July 31, 2023); Alcántara, supra note 85; Abhishek Nagaraj & Scott Stern, The Economics of Maps, 34 J. of Econ. Perspectives 196, 207-8 (2020), https://pubs.aeaweb.org/doi/pdfplus/10.1257/jep.34.1.196 .

- Alcántara, supra note 85.

- Lawmakers have also addressed such concerns through legislative efforts like the European Union’s Digital Markets Act (DMA), which went into effect in May 2023. See Regulation (EU) 2022/1925 of the European Parliament and of the Council on Contestable and Fair Markets in the Digital Sector and Amending Directives (EU) 2019/1937 and (EU) 2020/1828 (Digital Markets Act), Off. J. of the E.U. (Sept. 14, 2022), https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/HTML/?uri=CELEX:32022R1925&from=EN ; see id. at art. 54. Under the DMA, large online platforms that qualify are designated as “gatekeepers” and must comply with a series of obligations—including providing third parties “effective interoperability” with their hardware and software features for free—that are intended to ensure fair and open digital markets. See id. at art. 6, para. 7. The DMA preamble explicitly references NFC technology, stating that preventing third-party access to functionalities like NFC could “significantly undermine” innovation and consumer choice. See id. at preamble, paras. 55-57. On September 6, 2023, the European Commission designated six gatekeepers under the DMA, including Apple and Alphabet. Digital Markets Act: Commission Designates Six Gatekeepers, Eur. Comm’n (Sept. 6, 2023), https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_23_4328 . A few years earlier, the German Parliament passed a similar law that gives payment service providers the right to access mobile device technical infrastructure like NFC, subject to an “appropriate fee” and under “appropriate access conditions.” Daniel Döderlein, Your Phone is Not Yours Except in Germany Thanks to a New Law, Forbes (May 3, 2020), https://www.forbes.com/sites/danieldoderlein/2020/05/03/your-phone-is-not-yours-except-in-germany-thanks-to-a-new-law/ . “This provision is sometimes referred to as Lex Apple Pay because its objective is widely understood to provide payment service providers access to Apple’s [NFC] chip.” Joe Sunderland, et al., Digital Markets Act – Impact Assessment Support Study, Annexes, at 330, Cullen Int’l, https://www.cullen-international.com/studies/2021/Digital-Markets-Act---Impact-assessment-support-study--executive-summary-and-synthesis-report.html . In the U.S., federal legislation similar to the DMA has also been introduced in Congress. For example, the American Innovation and Choice Online Act would prohibit large online platforms from unfairly preferencing their own products, services, or lines of business, and from retaliating against platform users who report concerns, among other things. See S. 2992, 117th Cong. (2021-2022); see also Tom Romanoff, The American Innovation and Choice Online Act: What it Does and What it Means, Bipartisan Pol’y Ctr. (Jan. 20, 2022), https://bipartisanpolicy.org/explainer/s2992/ .

- Determination, Applications for Authorisation A91546 & A91547, Austl. Competition & Consumer Comm’n (Mar. 31, 2017), https://www.accc.gov.au/system/files/public-registers/documents/D17%2B40724.pdf .

- See Antitrust: Commission Sends Statement of Objections to Apple Over Practices Regarding Apple Pay, Eur. Comm’n (May 2, 2022), https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/IP_22_2764 . The action remains pending.

- See Amended Class Action Complaint at 6-7, Affinity Credit Union v. Apple Inc., No. 4:22-cv-04174 (N.D. Ca. Oct. 28, 2022). The action remains pending.