Consumer Financial Protection Circular 2022-06

Unanticipated overdraft fee assessment practices

Question presented

Can the assessment of overdraft fees constitute an unfair act or practice under the Consumer Financial Protection Act (CFPA), even if the entity complies with the Truth in Lending Act (TILA) and Regulation Z, and the Electronic Fund Transfer Act (EFTA) and Regulation E?

Response

Yes. Overdraft fee practices must comply with TILA, EFTA, Regulation Z, Regulation E, and the prohibition against unfair, deceptive, and abusive acts or practices in Section 1036 of the CFPA.1 In particular, overdraft fees assessed by financial institutions on transactions that a consumer would not reasonably anticipate are likely unfair. These unanticipated overdraft fees are likely to impose substantial injury on consumers that they cannot reasonably avoid and that is not outweighed by countervailing benefits to consumers or competition. As detailed in this Circular, unanticipated overdraft fees may arise in a variety of circumstances. For example, financial institutions risk charging overdraft fees that consumers would not reasonably anticipate when the transaction incurs a fee even though the account had a sufficient available balance at the time the financial institution authorized the payment (sometimes referred to as “authorize positive, settle negative (APSN)”).

Background

An overdraft occurs when consumers have insufficient funds in their account to cover a transaction, but the financial institution nevertheless pays it. Unlike non-sufficient funds penalties, where a financial institution incurs no credit risk when it returns a transaction unpaid for insufficient funds, clearing an overdraft transaction is extending a loan that can create credit risk for the financial institution. Most financial institutions today charge a flat per-transaction fee, which can be as high as $36, for overdraft transactions, regardless of the amount of credit risk, if any, that they take.

Overdraft programs started as courtesy programs under which financial institutions would decide on a manual, ad hoc basis to pay particular check transactions for which consumers lacked funds in their deposit accounts rather than to return the transactions unpaid, which may have other negative consequences for consumers. Although Congress did not exempt overdraft programs offered in connection with deposit accounts when it enacted TILA,2 the Federal Reserve Board (Board) in issuing Regulation Z in 1969 created a limited exemption from the new regulation for financial institutions’ overdraft programs at that time (also then commonly known as “bounce protection programs”).3

Overdraft programs in the 1990s began to evolve away from this historical model in a number of ways. One major industry change was a shift away from manual ad hoc decision-making by financial institution employees to a system involving heavy reliance on automated programs to process transactions and to make overdraft decisions. A second was to impose higher overdraft fees. In addition, broader changes in payment transaction types increased the impacts of these other changes on overdraft programs. In particular, debit card use expanded dramatically, and financial institutions began charging overdraft fees on debit card transactions, which, unlike checks, are authorized by financial institutions at the time consumers initiate the transactions. And unlike checks, there are no similar potential negative consequences to consumers from a financial institution’s decision to decline to authorize a debit card transaction.

As a result of these operational changes, overdraft programs became a significant source of revenue for banks and credit unions as the volume of transactions involving checking accounts increased due primarily to the growth of debit cards.4 Before debit card use grew, overdraft fees on check transactions formed a greater portion of deposit account overdrafts. Debit card transactions presented consumers with markedly more chances to incur an overdraft fee when making a purchase because of increased acceptance and use of debit cards for relatively small transactions (e.g., fast food and grocery stores).5 Over time, revenue from overdraft increased and began to influence significantly the overall pricing structure for many deposit accounts, as providers began relying heavily on back-end pricing while eliminating or reducing front-end pricing (i.e., “free” checking accounts with no monthly fees).6

As a result of the rapid growth in overdraft programs, Federal banking regulators expressed increasing concern about consumer protection issues and began a series of issuances and rulemakings. In the late 2000s as the risk of significant harm regarding overdraft programs continued to mount despite the increase in regulatory activity, Federal agencies began exploring various additional measures with regard to overdraft, including whether to require that consumers affirmatively opt in before being charged for overdraft programs. In February 2005, the Board, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC), the National Credit Union Administration (NCUA), and the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC) issued Joint Guidance on Overdraft Protection Programs.7 In May 2005, the Board amended its Regulation DD (which implements the Truth in Savings Act) to expand disclosure requirements and revise periodic statement requirements for institutions that advertise their overdraft programs to provide aggregate totals for overdraft fees and for returned item fees for the periodic statement period and the year to date.8 In May 2008, the Board along with the NCUA and the now-defunct Office of Thrift Supervision proposed to exercise their authority to prohibit unfair or deceptive acts or practices under section 5 of the Federal Trade Commission Act (FTC Act)9 to prohibit institutions from assessing any fees on a consumer’s account in connection with an overdraft program, unless the consumer was given notice and the right to opt out of the service, and the consumer did not opt out.10 In January 2009, the Board finalized a Regulation DD rule that, among other things, expanded the previously mentioned disclosure and periodic statement requirements for overdraft programs to all depository institutions (not just those that advertise the programs).11 In addition, although the three agencies did not finalize their FTC Act proposal, the Board ultimately adopted an opt-in requirement for overdraft fees assessed on ATM and one-time debit card transactions under Regulation E (which implements EFTA)12 in late 2009.13

More recently, Federal financial regulators, such as the CFPB, the Board, and the FDIC, issued guidance around practices that lead to the assessment of overdraft fees. In 2010, the FDIC issued Final Overdraft Payment Supervisory Guidance on automated overdraft payment programs and warned about product over-use that may harm consumers.14 In 2015, the CFPB issued public guidance explaining that one or more institutions had acted unfairly and deceptively when they charged certain overdraft fees.15 Beginning in 2016, the Board publicly discussed issues with unfair fees related to transactions that authorize positive and settlenegative.16 In July 2018, the Board issued a Consumer Compliance Supervision Bulletin finding certain overdraft fees assessed based on the account’s available balance to be an unfair practice in violation of section 5 of the FTC Act.17 In June 2019, the FDIC issued its Consumer Compliance Supervisory Highlights and raised risks regarding certain use of the available balance method.18 In September 2022, the CFPB found that a financial institution had engaged in unfair and abusive conduct when it charged APSN fees.

Analysis

Violations of the Consumer Financial Protection Act

The CFPA prohibits conduct that constitutes an unfair act or practice. An act or practice is unfair when: (1) It causes or is likely to cause substantial injury to consumers that is not reasonably avoidable by consumers; and (2) The injury is not outweighed by countervailing benefits to consumers or to competition.19

An unanticipated overdraft fee occurs when financial institutions assess overdraft fees on transactions that a consumer would not reasonably expect would give rise to such fees. The CFPB has observed that in many circumstances, financial institutions have created serious obstacles to consumers making informed decisions about their use of overdraft services. Overdraft practices are complex—and differ among institutions. Even if a consumer closely monitors their account balances and carefully calibrates their spending in accordance with the balances shown, they can easily incur an overdraft fee they could not reasonably anticipate because financial institutions use processes that are unintelligible for many consumers and that consumers cannot control. Though financial institutions may provide disclosures related to their transaction processing and overdraft assessment policies, these processes are extraordinarily complex, and evidence strongly suggests that, despite such disclosures, consumers face significant uncertainty about when transactions will be posted to their account and whether or not they will incur overdraft fees.20

For example, even when the available balance on a consumer’s account—that is, the balance that, at the time the consumer initiates the transaction, would be displayed as available to the consumer—is sufficient to cover a debit card transaction at the time the consumer initiates it, the balance on the account may not be sufficient to cover it at the time the debit settles. The account balance that is not reduced by any holds from pending transactions is often referred to as the ledger balance. The available balance is generally the ledger balance plus any deposits that have not yet cleared but are made available, less any pending (i.e., authorized but not yet settled) debits. Since consumers can easily access their available balance via mobile application, online, at an ATM, or by phone, they reasonably may not expect to incur an overdraft fee on a debit card transaction when their balance showed there were sufficient available funds in the account to pay the transaction at the time they initiated it. Such transactions, which industry commonly calls “authorize positive, settle negative” or APSN transactions, thus can give rise to unanticipated overdraft fees.

This Circular highlights potentially unlawful patterns of financial institution practices regarding unanticipated overdraft fees and provides some examples of practices that might trigger liability under the CFPA. This list of examples is illustrative and not exhaustive.21 Enforcers should closely scrutinize whether and when charging overdraft fees may contravene Federal consumer financial law. A “substantial injury” typically takes the form of monetary harm, such as fees or costs paid by consumers because of the unfair act or practice. In addition, actual injury is not required; a significant risk of concrete harm is sufficient.22 An injury is not reasonably avoidable by consumers when consumers cannot make informed decisions or take action to avoid that injury. Injury that occurs without a consumer’s knowledge or consent, when consumers cannot reasonably anticipate the injury, or when there is no way to avoid the injury even if anticipated, is not reasonably avoidable. Finally, an act or practice is not unfair if the injury it causes or is likely to cause is outweighed by its consumer or competitive benefits.

Charging an unanticipated overdraft fee may generally be an unfair act or practice. Overdraft fees inflict a substantial injury on consumers. Such fees can be as high as $36; thus consumers suffer a clear monetary injury when they are charged an unexpected overdraft fee. Depending on the circumstances of the fee, such as when intervening transactions settle against the account or how the financial institution orders the transactions at the end of the banking day, consumers could be assessed more than one such fee, further exacerbating the injury. These overdraft fees are particularly harmful for consumers, as consumers likely cannot reasonably anticipate them and thus plan for them.

As a general matter, a consumer cannot reasonably avoid unanticipated overdraft fees, which by definition are assessed on transactions that a consumer would not reasonably anticipate would give rise to such fees. There are a variety of reasons consumers might believe that a transaction would not incur an overdraft fee, because financial institutions use complex policies to assess overdraft fees that are likely to be unintelligible to many consumers. These policies include matters such as the timing gap between authorization and settlement and the significance of that gap, the amount of time a credit may take to be posted on an account, the use of one kind of balance over another for fee calculation purposes, or the order of transaction processing across different types of credit and debits. Mobile banking and the widespread use of debit card transactions could create a consumer expectation that account balances can be closely monitored. Consumers who make use of these tools may reasonably think that the balance shown in their mobile banking app, online, by telephone, or at an ATM, for example, accurately reflects the balance that they have available to conduct a transaction and, therefore, that conducting the transaction will not result in being assessed one or more overdraft fees. But unanticipated overdraft fees are caused by often convoluted settlement processes of financial institutions that occur after the consumer enters into the transaction, the intricacies of which are explained only in fine print, if at all.

Consumers are likely to reasonably expect that a transaction that is authorized at point of sale with sufficient funds will not later incur overdraft fees. Consumers may understand their account balance based on keeping track of their expenditures, or increasingly through the use of mobile and online banking, where debit card transactions are immediately reflected in mobile and online banking balances. Consumers may reasonably assume that when they have sufficient available balance in their account at the time they entered into the transaction, they will not incur overdraft fees for that transaction. But consumers generally cannot reasonably be expected to understand and thereby conduct their transactions to account for the delay between authorization and settlement—a delay that is generally not of the consumers’ own making but is the product of payment systems. Nor can consumers control the methods by which the financial institution will settle other transactions—both transactions that precede and that follow the current one—in terms of the balance calculation and ordering processes that the financial institution uses, or the methods by which prior deposits will be taken into account for overdraft fee purposes.23

The injury from unanticipated overdraft fees likely is not outweighed by countervailing benefits to consumers or competition. Where a financial institution has authorized a debit card transaction, the institution is obligated to pay the transaction, irrespective of whether an overdraft fee is assessed. Access to overdraft programs therefore is not a countervailing benefit to the assessment of overdraft fees in such unanticipated circumstances. Nor does it seem plausible that the ability to generate revenue through unanticipated overdraft fees allows for lower front-end account or maintenance fees that would outweigh the substantial injury in terms of the total costs of the unanticipated overdraft fees charged to consumers. Indeed, in recent months, several large banks have announced plans to entirely eliminate or significantly reduce overdraft fees.24 In other consumer finance contexts, research has shown that where back-end fees decreased, companies did not increase front-end prices in an equal amount.25 But even a corresponding front-end increase in pricing would generally not outweigh the substantial injury from unexpected back-end fees.

As for benefits to competition, economic research suggests that shifting the cost of products from front-end prices to back-end fees risks harming competition by making it more difficult to compete on transparent front-end fees and reduces the portion of the overall cost that is subject to competitive price shopping.26 This is especially the case, where, as here, the fees likely cannot reasonably be anticipated by consumers. Given that back-end fees are likely to be harmful to competition, it may be difficult for institutions to demonstrate countervailing benefits of this practice. A substantial injury that is not reasonably avoidable and that is not outweighed by such countervailing benefits would trigger liability under existing law.

Examples of Potential Unfair Acts or Practices Involving Overdraft Fees that Consumers Would Not Reasonably Anticipate

In light of the complex systems that financial institutions use for overdraft, such as different balance calculations and transaction processing orders, enforcers should scrutinize situations likely to give rise to unanticipated overdraft fees. The following are non-exhaustive examples of such practices that may warrant scrutiny.

Unanticipated overdraft fees can occur on “authorize positive, settle negative” or APSN transactions, when financial institutions assess an overdraft fee for a debit card transaction where the consumer had sufficient available balance in their account to cover the transaction at the time the consumer initiated the transaction and the financial institution authorized it, but due to intervening authorizations, settlement of other transactions (including the ordering in which transactions are settled), or other complex processes, the financial institution determined that the consumer’s balance was insufficient at the time of settlement.27 These unanticipated overdraft fees are assessed on consumers who are opted in to overdraft coverage for one-time debit card and ATM transactions, but they likely did not expect overdraft fees for these transactions.

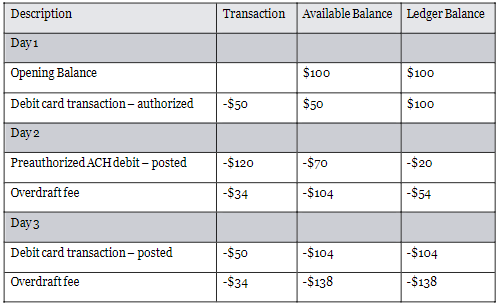

The following table (Table 1) shows an example of unanticipated overdraft fees involving a debit card transaction with an intervening debit transaction. The consumer is charged an overdraft fee even though the consumer’s available balance was positive at the time the consumer entered into the debit card transaction.

Table 1: Unanticipated Overdraft Fee Assessed Through APSN with Intervening Debit Transaction

For example, as illustrated above in Table 1, on Day 1, a consumer has $100 in her account available to spend based on her available balance displayed. The consumer enters into a debit card transaction that day for $50. On Day 2, a preauthorized ACH debit that the consumer had authorized previously for $120 is settled against her account. The financial institution charges the consumer an overdraft fee. On Day 3, the debit card transaction from Day 1 settles, but by that point the consumer’s account balance has been reduced by the $120 ACH debit settling and the $34 overdraft fee, leaving the balance as negative $54 using ledger balance, or negative $104 using available balance. When the $50 debit card transaction settles against the negative balance, the financial institution charges the consumer another overdraft fee. Consumers may not reasonably expect to be charged this second overdraft fee, based on a debit card transaction that has been authorized with a sufficient account balance. The consumer may reasonably expect that if their account balance shows sufficient funds for the transaction just before entering into the transaction, as reflected in their account balance in their mobile application, online, at an ATM, or by telephone, then that debit card transaction will not incur an overdraft fee. Consumers may not reasonably be able to navigate the complexities of the delay between authorization and settlement of overlapping transactions that are processed on different timelines and impact the balance for each transaction. If consumers are presented with a balance that they can view in real-time, they are reasonable to believe that they can rely on it, rather than have overdraft fees assessed based on the financial institution’s use of different balances at different times and intervening processing complexities for fee-decisioning purposes.

Certain financial institution practices can exacerbate the injury from unanticipated overdraft fees from APSN transactions by assessing overdraft fees in excess of the number of transactions for which the account lacked sufficient funds. In these APSN situations, financial institutions assess overdraft fees at the time of settlement based on the consumer’s available balance reduced by debit holds, rather than the consumer’s ledger balance, leading to consumers being assessed multiple overdraft fees when they may reasonably have expected only one.

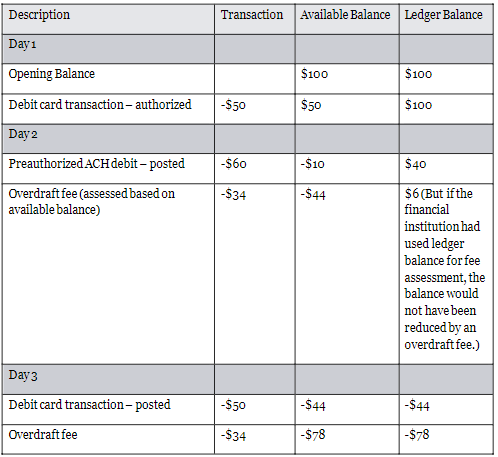

The following table (Table 2) shows an example of how financial institutions may process overdraft fees on two transactions. The consumer is charged an additional overdraft fee when the financial institution assesses fees based on available balance, because the financial institution is assessing an overdraft fee on a transaction which the institution has already used in making a fee decision on another transaction. By contrast, the consumer would not have been charged the additional overdraft fee if the financial institution used ledger balance.

Table 2: Unanticipated Overdraft Fee Assessed Through APSN by Financial Institution Using Available Balance for Fee Decision

For example, as illustrated above in Table 2, on Day 1, a consumer has $100 in her account, which is the amount displayed on her online account. The consumer enters into a debit card transaction that day for $50. On Day 2, a preauthorized ACH debit that the consumer had authorized previously for $60 is settled against her account. Because the debit card transaction from Day 1 has not yet settled, the consumer’s ledger balance, prior to posting of the $60 ACH debit, is still $100. But some financial institutions will consider the consumer’s balance for purposes of an overdraft fee decision as $50, as already having been reduced by the not-yet-settled debit card transaction from Day 1, and thus the settlement of the $60 ACH debit will take the account negative and incur an overdraft fee. On Day 3, the debit card transaction from Day 1 settles, but by that point the consumer’s balance has been reduced by the settlement of the $60 ACH debit plus the overdraft fee for that transaction. If the overdraft fee is $34, the consumer’s account has $6 left in ledger balance. The $50 debit card transaction then settles, overdrawing the account and the financial institution charges the consumer an overdraft fee. The consumer would not expect two overdraft fees, since her account balance showed sufficient funds at the time she entered into the debit card transaction to cover either one of them. But in this example, the financial institution charged two overdraft fees, by assessing an overdraft fee on a transaction which the institution has already used i making a fee decision on another transaction. By contrast, a financial institution using ledger balance for the overdraft fee decision would have charged only one overdraft fee.

1 CFPA § 1036, 12 U.S.C. 5536.

2 Pub. L. 90–321, 82 Stat. 146 (May 29, 1968), codified as amended at 15 U.S.C. 1601 et seq.

3 34 FR 2002 (Feb . 11, 1969). See also, e.g., 12 CFR1026.4(c)(3) (excluding charges imposed by a financial institution for paying items that overdraw an account from the definition of “finance charge,” unless the payment of such items and the imposition of the charge were previously agreed upon in writing); 12 CFR 1026.4(b )(2) (providing that any charge imposed on a checking or other transaction account is an example of a finance charge only to the extent that the charge exceeds the charge for a similar account without a credit feature).

4 CFPB, Study of Overdraft Programs: A White Paper of Initial Data Findings, at 16 (June 2013), available at http://files.consumerfinance.gov/f/201306_cfpb_whitepaper_overdraftpractices.pdf

5 Id. at 11-12.

6 Id. at 16-17.

7 70 FR 9127 (Feb. 24, 2005).

8 70 FR 29582 (May 24, 2005).

9 15 U.S.C. 45.

10 73 FR 28904 (May 19, 2008).

11 74 FR 5584 (Jan. 29, 2009). The rule also addressed balance disclosures that institutions provide to consumers through automated systems.

12 Pub . L. 90–321, 92 Stat. 3728 (Nov. 10, 1978), codified as amended at 15 U.S.C. 1693 et seq.

13 74 FR 59033 (Nov. 17, 2009).

14 FDIC, Final Overdraft Payment Supervisory Guidance, FIL-81-2010 (Nov . 24, 2010), available at https://www.fdic.gov/news/financial-institution-letters/2010/fil10081.pdf .

15 CFPB Supervisory Highlights, Winter 2015, at 8-9, available at https://files.consumerfinance.gov/f/201503_cfpb_supervisory-highlights-winter-2015.pdf .

16 Interagency Overdraft Services Consumer Compliance Discussion (Nov. 9, 2016), available at https://www.consumercomplianceoutlook.org/outlook-live/2016/interagency-overdraft-services-consumer-compliance-discussion / (follow “Presentation Slides” hyperlink), at slides 20-21.

17 See Federal Reserve Board, Consumer Compliance Supervision Bulletin 12 (July 2018), available at https://www.federalreserve.gov/publications/files/201807-consumer-compliance-supervision-bulletin.pdf (stating that it had identified “a UDAP violation ... when a bank imposed overdraft fees on [point-of-sale] transactions based on insufficient funds in the account’s available balance at the time of posting, even though the bank had previously authorized the transaction based on sufficient funds in the account’s available balance when the consumer entered into the transaction”).

18 FDIC, Consumer Compliance Supervisory Highlights 2-3 (June 2019), available at https://www.fdic.gov/regulations/examinations/consumercomplsupervisoryhighlights.pdf?source=govdelivery&utm_medium=email&utm_source=govdelivery . The agency referred to the available balance method as assessing overdraft fees based on the consumer’s “available balance” rather than the consumer’s “ledger balance.” The agency stated that use of the available balance method “creates the possibility of an institution assessing overdraft fees in connection with transactions that did not overdraw the consumer’s account,” and that entities could mitigate risk “[w]hen using an available balance method, [by] ensuring that any transaction authorized against a positive available balance does not incur an overdraft fee, even if the transaction later settles against a negative available balance.”

19 CFPA §§ 1031, 1036, 12 U.S.C. 5531, 5536.

20 See, e.g., CFPB, Consumer voices on overdraft programs (Nov. 2017), available at https://files.consumerfinance.gov/f/documents/cfpb_consumer-voices-on-overdraft-programs_report_112017.pdf .

21 Depending on the circumstances, assessing overdraft fees may also implicate deceptive or abusive acts or practices, or other unfair acts or practices under CFPA §§ 1031, 1036, 12 U.S.C. 5531, 5536.

22 See F.T.C. v. Wyndham Worldwide Corp., 799 F.3d 236, 246 (3d Cir. 2015)

23 While financial institutions must obtain a consumer’s “opt-in” before the consumer can be charged overdraft fees on one-time debit card and ATM transactions, 12 CFR 1005.17(b), this does not mean that the consumer intended to make use of those services in these transactions where the consumer believed they had sufficient funds to pay for the transaction without overdrawing their account.

24 CFPB, “Comparing overdraft fees and policies across banks” ( Feb. 10, 2022), available at https://www.consumerfinance.gov/about-us/blog/comparing-overdraft-fees-and-policies-across-banks/.

25 Sumit Agarwal, Souphala Chomsisengphet, Neale Mahoney, & Johannes Stroebel, Regulating Consumer Financial Products: Evidence from Credit Cards, Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol . 130, Issue 1 (Feb. 2015), pp. 111-64, at p.5 & 42-43, available at https://academic.oup.com/qje/article/130/1/111/2338025?login=true .

26 Xavier Gabaix & David Laibson, Shrouded Attributes, Consumer Myopia, and Information Suppression in Competitive Markets, Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 121, Issue 2 (May 2006), pp.505-40, available at https://pages.stern.nyu.edu/~xgabaix/papers/shrouded.pdf ; see also Steffen Huck & Brian Wallace, The impact of price frames on consumer decision making: Experimental evidence (2015), available at https://www.ucl.ac.uk/~uctpbwa/papers/price-framing.pdf; Agarwal et al., Regulating Consumer Financial Products, supra note 25; Sumit Agarwal, Souphala Chomsisengphet, Neale Mahoney, & Johannes Stroebel, A Simple Framework for Establishing Consumer Benefits from Regulating Hidden Fees, Journal of Legal Studies, Vol . 43, Issue S2 (June 2014), pp.S239-52, available at https://nmahoney.people.stanford.edu/sites/g/files/sbiybj23976/files/media/file/mahoney_hidden_fees_jls.pdf .

27 See, e.g., CFPB Supervisory Highlights, supra note 15; Interagency Overdraft Services Consumer Compliance Discussion, supra note 16; Federal Reserve Board, Consumer Compliance Supervision Bulletin, supra note 17; FDIC, Consumer Compliance Supervisory Highlights, supra note 18.